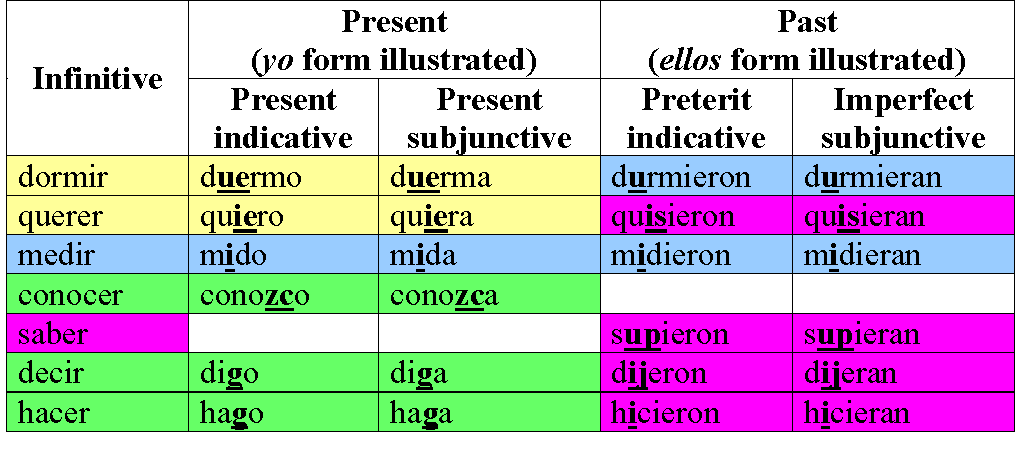

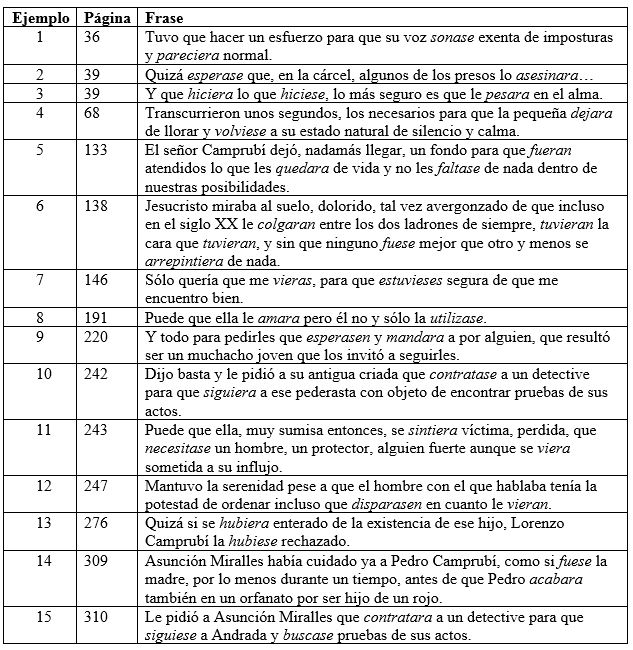

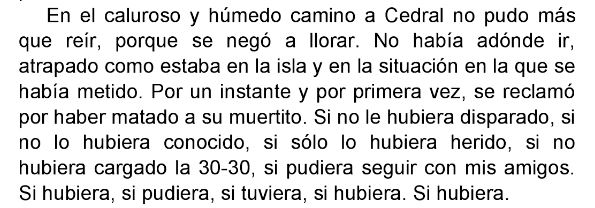

A few months ago I wrote to Jordi Sierra i Fabra, the Spanish author who writes the marvelous “Inspector Mascarell” series of detective novels set in Franco-era Barcelona. I have long been intrigued, or even obsessed, by Sierra i Fabra’s use of the Spanish imperfect subjunctive, and wanted to know if he was manipulating this grammatical feature deliberately. My letter included the table from my most recent post on this subject in which I listed all the sentences I’d found in his recent novel Diez días de junio that combine the two versions of the imperfect subjunctive, such as Puede que ella le amara pero él no y sólo la utilizase.

I didn’t expect to hear back from Sr. Sierra i Fabra; he is one of Spain’s most popular writers and appears to be frantically busy. According to his Wikipedia page, he has published 57 novels, 20 books on the history of rock and roll, 38 biographies of rock and roll musicians, 3 books of poetry, and 115 children’s books. He also runs a foundation to support young writers, with offices in Barcelona and Medellín, and has won 14 literary and cultural prizes.

Nevertheless, Sierra i Fabra took the time to send me a very sweet reply, and didn’t seem to resent that some crazy linguist in New York was obsessed with his verbs. The gist of his answer was that not only had he not manipulated the imperfect subjunctive deliberately, but also, he had no idea what it was. He explained that he left school when he was sixteen and had never studied Spanish grammar. Again, he was very kind, writing:

Celebro que me leas. Es un honor. Y celebro haberte causado esas dudas y esas preguntas sin pretenderlo. La vida tiene estas sorpresas.

Sierra i Fabra also wrote that he would like to meet me in person if he comes to New York. (He was undoubtedly just being polite.) Another recent novel of his, El gran sueño, is based in New York — like María Dueñas’s latest novel, Las hijas del capitán (meh), it’s about 19th century Spanish immigrants — so perhaps he will come here for some publicity?

Such a thrill…and, to me, it’s fascinating from a linguistic perspective that a pattern can be so frequent and yet not deliberate. I suppose we all have such ticks in our own writing, and that sometimes a weird outsider is the most equipped to catch them.

Regular readers of this blog know that I’m

Regular readers of this blog know that I’m

Seeing the subjunctive in action, after spending so much time researching and writing about it, was a real thrill. Plus, I love the poster — and I’m glad to say that Dra. Montserrat Salvador López, whose services it advertises, is listed as one of

Seeing the subjunctive in action, after spending so much time researching and writing about it, was a real thrill. Plus, I love the poster — and I’m glad to say that Dra. Montserrat Salvador López, whose services it advertises, is listed as one of