The COVID-19 pandemic has really done a number on my brain. I’m not talking about the notorious, long-lasting “brain fog” reported by many survivors of the coronavirus. I haven’t caught the disease and, God willing, will stay healthy until I eventually acquire immunity via vaccination. Rather, I’m talking about a general lack of sharpness. After months of anxiety and cabin fever spiked with a soupçon of political angst, everything I like to do with my normally nimble brain has become a bit harder.

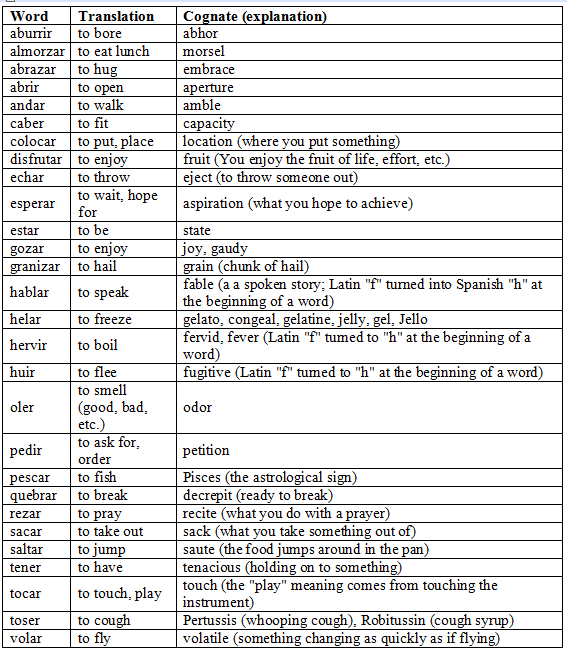

True, I managed to finish, proofread, and index my second book. Maybe that’s “enough to be going on with,” as the saying goes. I’ve also made some headway on my current research project, which concerns Spanish etymology, am gearing up to teach my first online class starting in a few weeks, and have resumed posting on this blog regularly after a substantial hiatus. Beyond Spanish, I’ve forced myself to stay on top of boring but necessary matters like insurance plans and household renovations. I’ve worked with my husband on various photographic projects; those of you who know me personally are aware that this is a vital part of my life and marriage. I’ve even learned how to shop for groceries online, a transition I’ve found surprisingly challenging, both practically and emotionally.

Where I’ve most felt the loss of sharpness is in my reading. I’ve always been an avid reader; my late grandmother always described me as “going around with a book under my arm.” I have happy childhood memories of hours on end spent curled up on the couch with a book. During my junior year of high school I kept track of every book I read, knowing that Harvard’s college application would ask for such a list. This worked out to a mind-blowing average of one serious book and one light book per day, if memory serves (perhaps it doesn’t), excluding books I reread, and also excluding (out of embarrassment) all 24 of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan novels, of which I particularly recommend the original Tarzan of the Apes as well as Son of Tarzan and Jane and the Foreign Legion.

This reading mania was only possible because I didn’t have much of a social life, which is pretty sad in retrospect. On the other hand, the many books I read, especially those I enjoyed over and over again, became part of my mental lexicon and taught me how to write by osmosis.

As a child and teenager I read fiction exclusively, dividing my time between meaty 19th century novels, often in translation (e.g. War and Peace and The Count of Monte Cristo), and light 20th century fiction. As an adult I have increasingly read non-fiction, particularly history and biography. I still enjoy light modern fiction but have yet to develop a taste for more serious modern writers such as Paul Auster and John Updike. In recent years I have added light Spanish fiction to the mix as an enjoyable way to continue to build my vocabulary and fluency.

During the pandemic, however, I have found it extremely difficult to muster the focus needed to tackle non-fiction, Spanish, or even, for the most part, novels I haven’t read before. Instead I’ve primarily reread light fiction voraciously, as a kind of mental “comfort food.” This includes all the Jane Austen, Dick Francis, Stephen King, and C. S. Forester novels on my bookshelf, much of the Harry Potter series, some P.D. James, and All Creatures Great and Small, just in time for the new BBC series.

The few non-fiction books I’ve been able to complete, such as Barack Obama’s memoir, have concerned contemporary politics. The one Spanish novel I’ve read, the 11th in my beloved Inspector Mascarell series, took me ages to get into. The fiction I’ve read for the first time has also been light, such as Louise Penny detective novels.

Which brings me to Meg Cabot. Best known for her Princess Diaries series, Cabot is a prolific author who mostly writes for young adults. I harbor the idiosyncratic conviction that her epistolary novel Boy Meets Girl (written for adults) is a work of genius, and am also fond of All-American Girl, which gave me some insight into the artistic process. Of course I reread both of these early in the pandemic. So when my daughter-in-law told me that she used to be into Cabot’s Mediator series, about a teenager who can communicate with the dead, I checked all six Mediator books out of our local library (let’s hear it for curbside pickup!) and had myself a fun time. The first and third books were quite good, but my favorite has to be the sixth, Twilight, which features … drum roll … a paean to learning Spanish!

Specifically, in Twilight‘s climactic scene our heroine Suze has traveled back in time (another mediator ability) to meet “in the flesh” the hunky Jesse de Silva, who was murdered 150 years ago and has been haunting Suze’s bedroom since she moved to California. Suze is unable to understand a crucial conversation between Jesse and his would-be murderer, the nefarious Felix Diego, because — get this — she doesn’t speak Spanish! Suze’s fellow mediator and frenemy Paul translates for her, but first she muses, memorably:

“Why? Why had I taken French and not Spanish?”

There were so many things I liked about this scene. First, it was very funny: for me at least, probably for other Spanish teachers, and hopefully for other readers as well. Second, it was exciting. Suze and Jesse’s relationship had been building over the past five novels, and its fate would depend on the showdown between Jesse and Diego. Third, it was educational. How many young adults today know about the Spanish period in California history? Finally, it showcased the utility of learning Spanish, albeit in a weird context. I hope that this scene inspired some Mediator fans to study the language, or to take their ongoing studies more seriously.

I don’t know whether Cabot speaks Spanish, but I do appreciate her speaking up for my favorite language. ¡Gracias, Meg!