Never having caught a fish in my life, I certainly didn’t imagine that I would ever write a blog post about our aquatic pals, let alone two. Nevertheless this is my second post on the topic. I guess everything is more interesting in Spanish.

As I explained in my first fish post back in 2016, Spanish has two words for fish: pez for a live fish and pescado for one that you see in a pescadería (fish store), supermarket, or restaurant. The verb pescar means ‘to fish’ and pescado is its past participle. So a pescado is simply a pez that has been fished, or caught.

Pez and pescado were at the root of an amusing incident that took place while I was visiting my grandkids in May. This was during the first wave of COVID-19 in the Northeast and my grandsons’ classes had gone online. My younger grandson’s Montessori kindergarten had a weekly Spanish lesson via Zoom and we both thought it would be fun for me to sit in. I have to confess that I stayed out of camera range and fed Zachary answers to the teacher’s questions. (Wouldn’t you?) As you can imagine he was the star of the lesson, getting everything right and amazing the teacher…UNTIL the class started to go through a set of animal words and they got to ‘fish.’

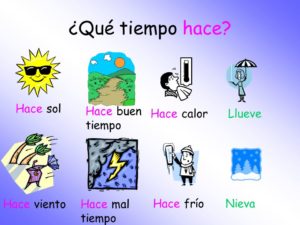

The teacher showed a picture of a pet fish in a bowl and asked if anyone knew ¿Qué es esto? Zachary was the only student to raise his hand. The teacher called on him and he said, correctly, Es un pez, to which the teacher replied No, es un pescado. They went back and forth a few times and the teacher held her ground.

During the rest of the lesson I noticed other mistakes in the teacher’s Spanish. She said that a ‘kangaroo’ was a cangarú, which is basically a Spanish rendering of the English word instead of the proper Spanish word canguro. She also made a gender mistake, saying el serpiente instead of la. Given the teacher’s impeccable accent I concluded that she was a heritage speaker, meaning someone who grew up speaking Spanish at home but never had a formal education in the subject. Such speakers can have gaps in their knowledge.

According to Prof. Zyzik’s comment on this blog, heritage speakers are more prone to gender errors when using words such as serpiente, which lack a telltale -a or -o ending. Kids make such errors as well.

When I was back home in New York the next week, my daughter told me that Zachary had tried to answer el pez again during Spanish class and was again shot down. At this point I decided to do some research, looking up pescado on the Real Academia Española’s online Diccionario de americanismos. The first bullet in the entry read:

Mx, Gu, Ho, ES, Ni, Pa, Cu, PR, Co, Ve, Ec, Pe, Bo, Py. Pez, ya esté dentro o fuera del agua, sea comestible o no.

That is, in a number of Latin American countries pescado can mean a fish ‘in or out of the water, and edible or not.” So now I know.

In retrospect this dialectal variation might also explain the restaurant painting that inspired my first pez/pescado post, which showed a so-called pescado that was in the water (though hooked on a line). Chances are it was painted by someone with a similar background to Zachary’s teacher.

Stay tuned for my next fish post, four years from now.

Stay tuned for my next fish post, four years from now.