While I’m not much of a “beach person” — I don’t like the heat! — the last few weeks I’ve been craving a beach day. It really wouldn’t feel like summer without going at least once. So on Saturday, a girlfriend and I visited lovely, peaceful Hammonasset State Park in Madison, CT. It hit the spot.

Just before leaving for the beach I received the long-anticipated “”Welcome to the fall semester” email from the Spanish language coordinators at Fordham University (this is where I teach). All of a sudden the first day of classes (Wednesday!) feels real. I’m sure my future students are going through the same mental process. I will be teaching two sections of second-semester Spanish, and getting to know a new textbook, Gente.

These end-of-the-season events have inspired me to review the summer’s activity on spanishlinguist.us. I’ve published 27 posts since the beginning of June, roughly 3 a week. My main focus (9 posts) has been on verbs, which are, or course, a Big Deal in Spanish. These include:

- three posts on the present tense: irregular yo verbs, why ver is only recently irregular, and why -ir verbs are special

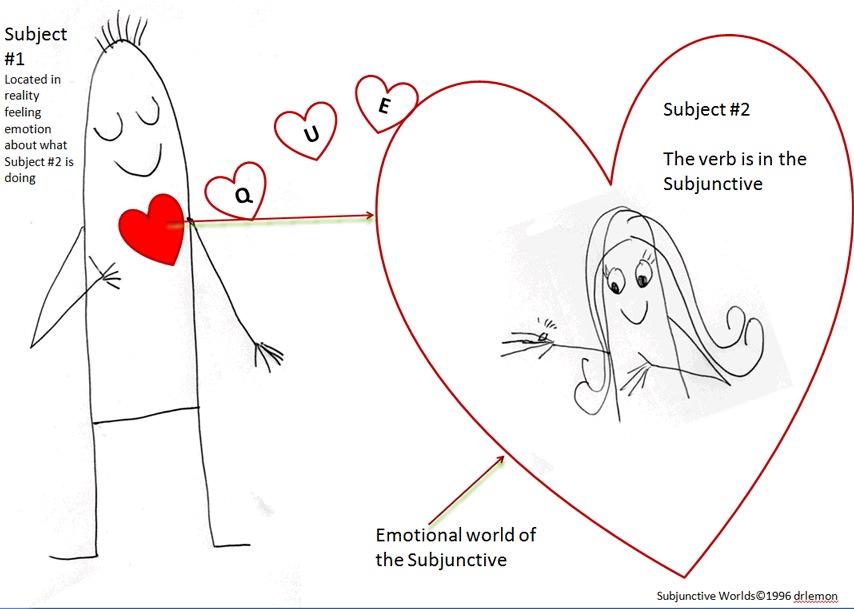

- two posts on the subjunctive: why there are two imperfect subjunctive conjugations, and why the subjunctive is so irregular.

- one post each about pretérito irregulars and the outcome of Latin verb tenses in Spanish.

Five posts have concerned vocabulary: Spanish slang, Spanish last names (women’s issues and patronymics) special vocabulary for disabilities, and new Spanish vocabulary from the economic crisis.

Five other posts have concerned the process of learning. Topics included mismatches between Spanish and English vocabulary (verging into grammar), the pedagogical value of reading popular fiction (including a terrific reading list), what I forgot when I didn’t speak Spanish for a few years, and the philosophy that “language is the only thing worth knowing even poorly.”

Four posts address Spanish spelling: accent marks, phonetic spelling (or not), x vs j, and x vs. cc.

Three posts address contemporary language issues: the minority languages of Spain, the high degree of metalinguistic awareness of normal Spanish speakers, and the political [in?]correctness of the language name Spanish.

This leaves two miscellaneous posts, on voseo and the surprising history of the word y “and“.

Four of the above posts were part of Spanish Friday: here, here, here, and here.

During the summer the blog has been enriched by comments from readers from around the world. I really appreciate this and encourage you to keep writing. Please feel free to suggest new topics you’d like this blog to address, or enhancements — I’ve added an RSS feed but still haven’t invested any time in Twitter or Facebook. I much prefer to “just write”, but if any bells and whistles would make a difference I will invest the time. I just added a snazzy new background (made with Wordle) and hope it renders well on your screen.

To subscribe by email, use the form on the right.

It’s been a great summer, and I’m looking forward to continuing into the new academic year.