I don’t know what inspired me to create the slideshow below. It popped into my head while I was driving home from the gym yesterday. I had a lot of fun fleshing it out last night and today. I hope you enjoy it, too.

Category Archives: Spanish in the world

My favorite Quora answer turns 100

Back in 2017, looking for ways to build my “platform,” I started answering questions about Spanish on Quora. Since then I have answered almost five hundred questions and accumulated over a hundred followers. Mostly I have had fun; really, anything that resembles teaching and gives me the opportunity to share my knowledge appeals to me.

In terms of platform-building there is no doubt that Quora has spread my writing; my answers have accumulated over 330,000 views and over 1250 upvotes.

I wrote my favorite Quora answer in 2018 in response to the question “Should I learn French or Spanish? I don’t care which language is more spoken. My reasons for learning a language encapsulate things like grammar, culture, history, arts, etc.“

Yesterday this answer received its 100th upvote. This makes me very happy because it was from the heart. I’ve copied it below, or you can read it on Quora here.

——————————————————————————————————————–

I feel passionate about this question because over the years, as a student and then teacher of Spanish, I’ve encountered so many prejudicial, knee-jerk, anti-Spanish attitudes. There was the high school classmate who told me that she chose French over Spanish because “only dirty people speak Spanish.”( She said this with a straight face and I believe she meant it.) There was my French-speaking (Swiss) cousin-in-law who was surprised when I told her that I considered Spanish art and literature to be on a par with, or superior than, their French counterparts. There was another French-speaking relative who thought it was funny that ¿Por qué?, the title of my book about Spanish, sounded, to him, like Porky. And then, of course, there is Donald Trump. While I haven’t heard him say anything good about French, he has been notoriously hostile to the Hispanic community, both abroad and in the United States.

I’d like to talk about a few of the topics that you mentioned in your question. In terms of culture, the outstanding thing about Spanish is that “Spanish culture” is more than Spanish — it is pan-Hispanic! While you “don’t care which language is more spoken”, the fact that Spanish is an official language in twenty-one countries, and is also widely spoken elsewhere (e.g. in the USA and Belize), means that the Spanish-speaking world is blessed with an enormous pool of potential talent. Thus great painters have come not only from Spain (think Velázquez) but also Mexico (Kahlo), Colombia (Botero), and the Hispanic community in the United States (Basquiat, whose mother was Puerto Rican). Nobel Prizes in literature have been won by writers from Spain, Chile, Guatemala, Peru, Chile, and Colombia.

I’m well-equipped to talk about Spanish grammar compared to French because I speak both languages and have, in fact, occasionally taught French even though Spanish is my “day job.” In my opinion Spanish grammar is more intellectually interesting than French. While the two languages share certain complexities compared to English, such as noun gender and multiple past tenses, Spanish has a more complex verb system — including, crucially, an actively used past tense subjunctive, whereas French only uses the present subjunctive — complications in its use of object pronouns, and the ser/estar contrast (both mean ‘to be’), which French lacks. It’s my impression that a lot of students sign up for Spanish because they think it’s easier than French but are sorely disappointed once they get past the early stages, in which the relatively straightforward spelling and pronunciation of Spanish do make Spanish somewhat simpler.

Finally, Spanish history rocks! It is essentially a series of conquests — the successive Roman, Germanic, Arabic, and Christian (re)conquests of Spain, followed by the Spanish conquests in the New World. Each of these has their own details and fascination, from Roman ruins to Arabic vocabulary to the fate of the indigenous peoples in the New World. (Did you know that even today, thirty million people in the Americas speak an indigenous language as their first language?)

So, if you are looking for a beautiful language spoken with pride, featuring a rich and varied culture, great books to read, and an intellectual linguistic challenge, you can’t go wrong with Spanish.

Latinx

I am working ferociously to finish correcting the page proofs for my new book, and to create an index (a painful task that I actually relish), so this is just a short post to say “hello” and share an interesting article I just read in the Washington Post about the word Latinx.

Latinx is an example of gender-neutral Spanish, one of several attempts to reduce or eliminate the use of -o and -os for masculine words and -a and -as for feminine word. In standard Spanish latino (note the lower-case l) is simultaneously masculine and neutral, so it can be used to identify either a Latino male or a Latino of unknown gender, as in La empresa espera contratar un latino para ese puesto ‘The company hopes to hire a Latino for that position.’ Likewise latinos refers to either a group of Latino males or a group of Latinos of mixed gender, male and female.

As in English, where the normative use of he has ceded ground to they, in today’s Spanish many speakers (and writers) try to avoid using gender-specific endings. In Spanish-speaking countries one often sees the @ character (called arroba in Spanish) used as a neuter vowel, as in this ‘Welcome refugees’ sign I saw in Valladolid a few years ago:

The x is also used as an alternative to the @; that’s the source of Latinx, which in my experience is found more often in the United States than in Spain, at least (I can’t generalize to other Spanish-speaking countries).

Anyway, the Washington Post just ran an op-ed, by their reporter José A. Del Real, asserting that “‘Latinx’ hasn’t even caught on among Latinos. It never will.” The article is behind a firewall, so here’s the key claim in case you can’t access the article:

“The label has not won wide adoption among the 61 million people of Latin American descent living in the United States. Only about 1 in 4 Latinos in the United States are familiar with the term, according to an August Pew Research Center survey. Just 3 percent identify themselves that way. Even politically liberal Latinos aligned with the broad cultural goals of the left are often reluctant to use it.”

The anti-Latinx reasons cited in the op-ed are its awkward pronunciation (especially in the plural), the preference among LGBTQ Latinos for Latine, and resistance to stamping a broad community with a single ethnic label. (The latter makes the term Hispano equally problematic.) The op-ed reports that “people of Latin American ancestry in the United States often prefer to describe themselves by referencing their specific countries of heritage, according to a 2019 Pew survey.”

True North (ern Spain)

Readers who find this post tl;dr can search ahead for the trip’s highlights: Tito Bustillo cave, As Catedrais beach, A Chavasqueira thermal baths, and a hike from Santiago de Compostela to Negreira.

I have just returned from my third trip to Spain in the last four years. The first trip, in 2016, was a linguistically-inspired itinerary through what I referred to as “Northern Spain.” To be more accurate, that trip went roughly from west to east across the northern half of the country, but not to the northern coast itself. Last year I went to Andalucía (southern Spain). So this year I determined to head to Spain’s true north: the provinces of Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque Country. It was a wonderful trip, combining natural beauty with man-made pleasures, and for the most part free of the hordes of tourists that plague Andalucía and Barcelona.

The trip involved three weeks of travel by train, car, and bus with three different companions: first my husband, then two friends (separately), one of whom I met through the website thelmandlouise.com. (I’ll use “we” generically in this post.) Below is a map of our itinerary. We went from east to west in order to wrap up the trip in the pilgrimage destination of Santiago de Compostela.

The trip began in San Sebastián, a small city famous for its perfect, shell-shaped main beach (appropriately named La Concha), and for its food culture. The weather was cool and drizzly, but as we hadn’t counted on swimming this wasn’t a real problem. We enjoyed walking along the beach, and took a fun and filling “Pintxos tour” with a guide we found on airbnb (pintxos are the Basque version of tapas). We splurged on an ocean-view room at a “Grand Dame” beach hotel, El hotel de Londrés y de Inglaterra.

Bilbao became a major tourist destination in 1997, when the Guggenheim Museum opened a Frank Gehry-designed branch there. The architecture is stunning. The art inside was another story: the museum does not have a comprehensive permanent collection, but rather specializes in temporary exhibitions, none of which we particularly cared for. However, we loved Richard Serra’s “The Matter of Time“, on display at the Guggenheim since 2005. It is a group of enormous steel sculptures that invite you to walk in and around them, as in a labyrinth. Bilbao’s older museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, was also worth seeing, especially this Zurburán.

By the way, we found Richard Serra exhibit so compelling that we brushed up on the artist’s life. We hadn’t realized that Serra is half-Spanish, or that his brother was the inspiration for the movie True Believer, one of our long-time favorite films, starring James Woods and a young Robert Downey, Jr.

Santander is a terrific city! It doesn’t have a historical district because it suffered a major fire in 1941, but it has a wonderful seaside location, with beaches, ferries, and walking paths, as well as top-notch shopping. Practically tourist-free, too (at least in early June). We had an enormous room at the Hotel Bahía, which is on the waterfront though not on a beach.

On the map above, Comillas is the unlabeled stop between Santander and Llanes. We stopped there to tour “El Capricho”, a house that the famous Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí built early in his career, in his late 20s. I’ve toured Gaudí’s better-known buildings in Barcelona but this was by far my favorite. It is drop-dead gorgeous on the outside, and very much a Gaudí building, with a fairy-tale tower and many nature-inspired forms. At the same time, the inside is welcoming and even practical: the kind of house that someone would actually want to live in. At least I would. PS I have been kicking myself for not buying the 1000-piece Ravensburger jigsaw puzzle sold in the Capricho’s gift shop. It turns out not to be available anywhere else!!! It would have fit in my suitcase if I had put the pieces in a bag and kept only the top of the box (with the picture). If you live in the NY area and are going to Comillas, let me know; maybe we can work something out. Edit from 2023: It turns out that Spanish museum gift shop loot, including “my” puzzle, can also be purchased online at mymuseumshop.com, but shipping to the U.S. would have been $50. So I had the puzzle sent to my hotel in Florence during a recent trip to Italy (this gave me an extra incentive to pack light) and am looking forward to eventually putting it together.

The small village of Llanes becomes a tourist mecca in the summer. Since it was still too cold to swim when we were there, things were pretty peaceful. We liked Llanes for its wonderful Hotel Don Paco (our favorite lodging from the entire trip), its small medieval section, and the wonderful walks we took along the seaside cliffs.

Llanes is also a good jumping-off point for trips into Picos de Europa. a Spanish national park that encompasses a spectacularly beautiful mountain range: “the Switzerland of Spain,” as it were. One day we attempted the popular “Garganta del Cares” trail. After hiking two miles from a satellite parking lot to the trailhead, we were defeated by the utter lack of shade on the trail itself. A second outing was more successful; we hiked a peaceful and mostly shady five-kilometer loop trail that began in the hamlet of San Pedro de Bedoya and continued through a series of fields and even smaller hamlets. (It’s the sixth “short walk for motorists” in Teresa Farino’s very useful book about Picos hiking.) We then spent the night at the Parador in Fuente Dé, which has a spectacular setting in the heart of the mountains, at the base of a popular gondola, but is an architectural failure. I can’t recommend the hotel, though the gondola was great.

En route from Llanes to Oviedo we visited the Cueva de Tito Bustillo, just outside Ribadesella, to see its famous prehistoric cave paintings. This was (and is) an extraordinary opportunity, given that only five tourists a week (!!!) are allowed to visit the Altamira cave, also in Northern Spain, and the Lascaux cave in France is closed to visitors. However, it is essential to reserve a spot on a specific tour well in advance. Our cave guide was excellent. Inter alia he pointed out how the prehistoric artists carefully located their drawings on parts of the cave wall whose bumps and dips added a realistic third dimension to their drawings, as in the full cheek on the horse’s head below.

Oviedo is a substantial city whose downtown boasts lively streets and also the lush and peaceful San Francisco park. Our favorite spot was the small but spectacular 9th-century Santa Maria de Naranco church, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

En route from Oviedo to Lugo, as we passed into Galicia, we stopped at another highlight of the trip: As Catedrais beach. At low tide you can walk out onto the sands and around the enormous, cathedral-like rocks. Just west of the beach we had a wonderful lunch at Restaurante La Yenka that featured scrumptious arroz negro (rice cooked with squid and squid ink). This was probably my favorite meal from the whole trip.

Judy (left) and Kat (right) at As Catedrais beach

Lugo is known for its Roman walls, which have been well-maintained over the centuries, so that you can walk all the way around the city on them. The city is small and pretty — a real jewel — though there isn’t much to see besides the walls. I liked the cathedral, and we also enjoyed hiking down from the city to the Minho River. We had a good walk along the river but then had to hike back up.

Ourense was originally settled because of its hot springs, and indeed these were the highlight of our visit there. The downtown thermal pool (As Burgas) was temporarily closed, so we walked across the river to A Chavasqueira, where we hung out with (mostly) local folks for whom soaking in these natural hot tubs is a regular activity. Conversation flowed in both Spanish and gallego: the local Romance language, and the source of Portuguese. I really hope that tourism doesn’t eventually overwhelm Ourense; I’d hate to think that use of these baths might have to be regulated. We also walked the dramatic up-and-down pedestrian loop of the city’s brilliant Puente del Milenio, or Millenium Bridge.

The entire tourist industry of Galicia, and much of its cultural identity, revolves around the pilgrimage destination of Santiago de Compostela. According to tradition, the apostle Saint James (Santiago) preached the Gospel in Spain, was buried in Galicia after being martyred in Jerusalem, and reappeared to lead a crucial (though mythical) battle during the Reconquista (the retaking of Spain from the Moors). His relics are now in the crypt of the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. Believers have been walking the Camino (‘road’) to the cathedral since the tenth century; they currently number annually in the hundreds of thousands, their numbers swelled by spiritual seekers in general as well as ambitious hikers.

The cathedral is currently being renovated. Luckily for us, the scaffolding is now off the building’s main facade, which fronts the Plaza de Obraidoro, where pilgrims take off their backpacks and/or park their bicycles, lie down, and feast their eyes on the splendid setting. The cathedral’s interior is now mostly inaccessible, which must be a disappointment to genuine pilgrims who have been looking forward to celebrating the Pilgrim Mass inside.

Besides admiring the cathedral’s sparkling-clean exterior and visiting its excellent museum, we played pilgrim ourselves by hiking the first stage of a popular add-on to the Camino that heads west through the Galician countryside, from Santiago to Finisterre on the Atlantic coast. Our 20-kilometer walk, which took us as far as Negreira, was a substantial challenge, but it was fun to follow the traditional waymarkers and to exchange greetings with walkers headed in both directions.

After these three trips I’m unlikely to visit Spain again anytime soon. My top Spanish-speaking travel priority is to see more of South America, starting with Argentina and Uruguay. Maybe next year!

Enjoying Andalusian Spanish

Since my travel companion during my recent trip to Andalucía doesn’t speak Spanish, I inevitably spoke mostly English while there. (I’m making up for this by speaking tons of Spanish while grading AP tests in Cincinnati.) Nevertheless, I had as many Spanish conversations with strangers as I possibly could, and also kept my ears open to expose myself, as much as possible, to Andalusian Spanish.

I’ve long been academically familiar with Andalusian Spanish, of course, meaning that I knew about its features from reading about them. And I knew that most of these features are shared with Latin American Spanish because, as demonstrated by Peter Boyd-Bowman, the Spaniards who immigrated to Latin America during the colonial period were disproportionately Andalusian. However, it was exciting to hear this kind of Spanish spoken around me in its home territory.

The Andalusian feature that means the most to me personally is the tendency to weaken or drop -s sounds at the ends of words and syllables. “Personally”, because my first linguistic research, as a Harvard undergraduate, was on this same phenomenon in Puerto Rican Spanish, and its possible consequences for subject pronoun usage in Puerto Rican Spanish. This research eventually led to an article published in Language, the prestigious flagship publication of the Linguistic Society of America, which as you can imagine was a healthy way to start my career. So every mimo (instead of mismo), gracia (instead of gracias), and so on sounded like a friendly blast from my past.

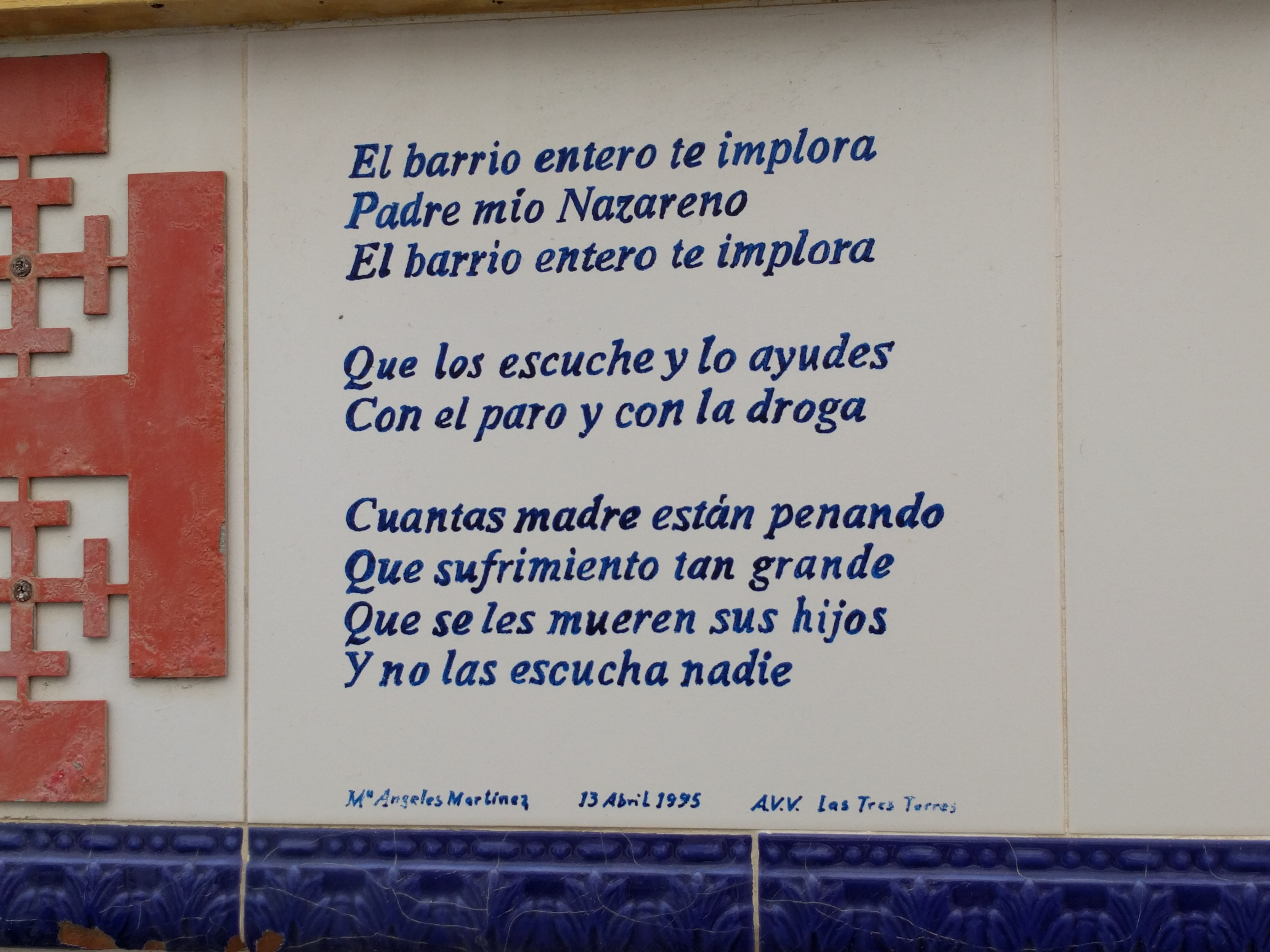

One hazard of dropping your s‘s frequently is that you can forget which words actually have them, and start to make mistakes in your spelling. A case in point is this poem, by María de los Ángeles Martínez González. which we saw set into a wall along a street in Cádiz. The words escuches and madres were cast in ceramic without their final s‘s, which you can see in this online version of the poem. This linguistic point aside, the poem is heart-breaking.

Another common Andalusian feature is the weakening and deletion of the d sound between two vowels. This is actually a downstream version of the historical process of “lenition” that, centuries ago, turned Latin t‘s into Spanish d‘s, and likewise Latin k and p sounds into Spanish g‘s and b‘s (vita > vida, focum > fuego, lupus > lobo).

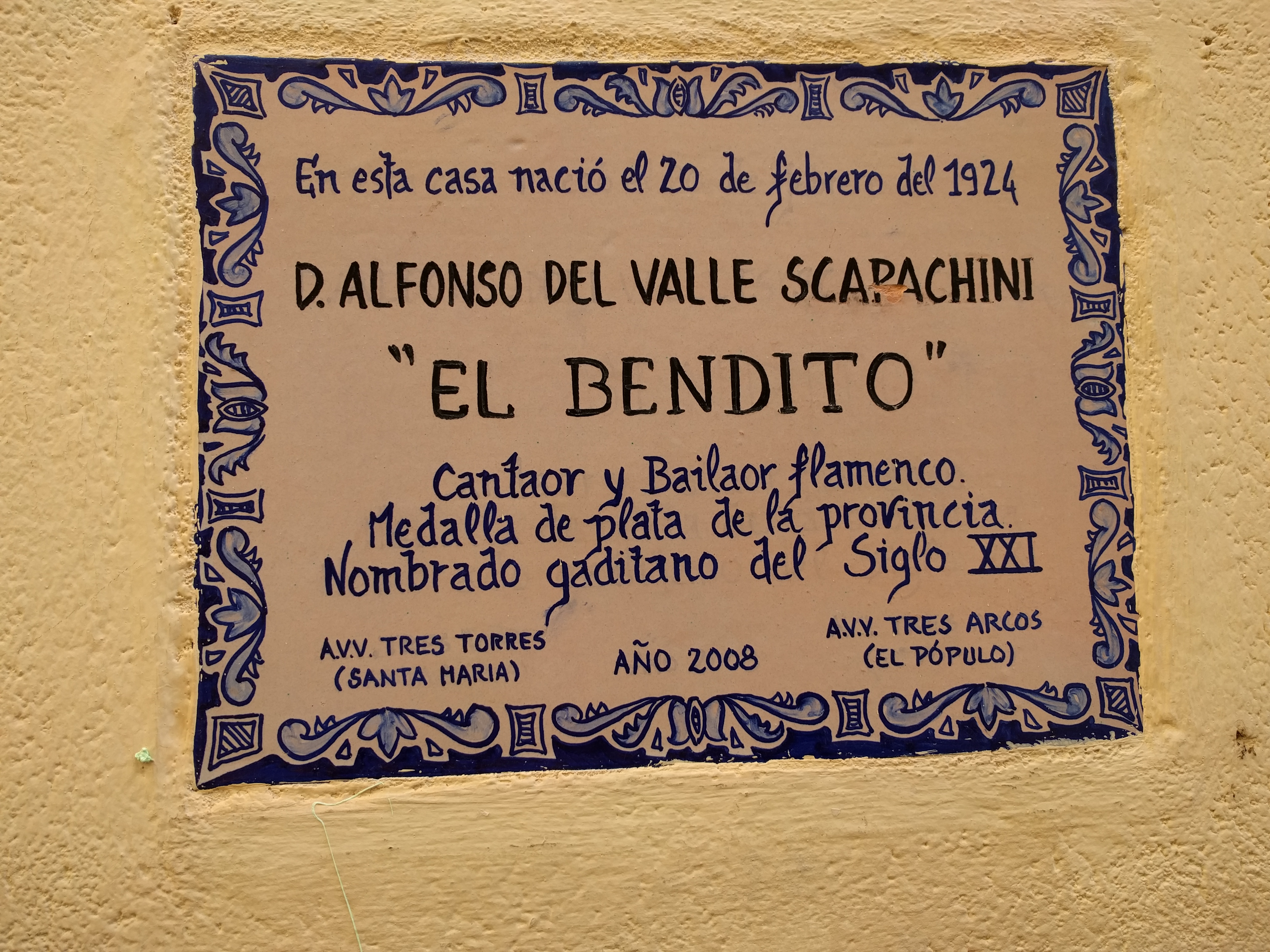

While on the same stroll through Cádiz I did a double-take when I saw what looked like another dialect-influenced spelling mistake on a historical marker memorializing a famous flamenco artist who was both a singer and a dancer: in standard Spanish, both a cantador and a bailador. Here, these two words were spelled without their d: cantaor and bailaor. After seeing the same spellings elsewhere I learned that they are, in fact, the legitimate terms for a flamenco singer and dancer. You can see the corresponding Real Academia dictionary entries here and here. So in this case lenition has gone legit.

Two final accentual anecdotes. First, struck by the non-Andalusian accent of one tchotchke seller I was chatting with in Granada, I asked if she was from out of town. She explained that she deliberately neutralized her accent when talking with non-Andalusians. Would you believe there’s a linguistic term for this? It’s called “linguistic accommodation”. Second, when I overheard a family group speaking in what I first thought was Italian and then realized was Spanish, I correctly inferred that they were from Argentina. Spanishlinguist scores! Actually, Argentinian Spanish is a softball dialect to identify…but still fun, especially when you hear it so far afield.

El burlador de Sevilla (Don Juan)

I took advantage of a 24-hour stopover in Madrid on the way home from my recent trip to Andalucía to see El burlador de Sevilla, the original Spanish play about Don Juan. According to University of Wisconsin professor R. John McCaw, the play’s exact origins are unknown. However, it was most likely written — in Madrid, not Sevilla — in the early 1620s, by the playwright Tirso de Molina.

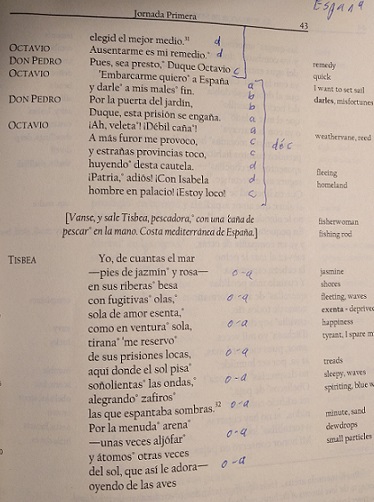

Since I majored in linguistics rather than Spanish, I had never read El burlador de Sevilla, and in fact didn’t know much about Golden Age theater. So before heading to Spain I bought a copy of Prof. McCaw’s edition of the play and studied it seriously. Just so you know what a good student I still am, after all these years out of school, here is a scan of one page showing how I marked up the book. What I learned was so interesting that I’d like to share it with you.

Golden Age playwrights like Tirso de Molina had to be incredibly skilled. They did what any playwright does — tell an exciting story, develop their characters, and so on — while at the same time fitting their Spanish into a set of specific rhyming patterns. As Prof. McCaw explains in his introduction, most of El burlador fits into one of six rhyming patterns, each defined by four parameters:

- the number of lines in the pattern;

- the number of syllables per line (playwrights “fudge” by merging or extending some syllables);

- the type of rhyme: whether consonants matter (consonance), as in the rhyme of España, engaña, and caña near the top of the page in the image above, or not (assonance), as in the sequence rosa…olas…sola…locas…ondas…sombras…alfójar…adora in Tisbea’s speech at the bottom of the page;

- the rhyming pattern within the lines, e.g. ABBA (lines 1 and 4 rhyme, also lines 2 and 3).

After marking up the entire text — this isn’t as crazy as it sounds, since the play is less then 100 pages long — I tallied how often each rhyming pattern was used. Here’s what I found:

- The most common pattern — the default, really — was the redondilla, four lines of eight syllables each with a consonant ABBA rhyming scheme.

- The second most common pattern was the romance, an indefinitely long sequence of eight-syllable lines with an assonant xAxAxA rhyming scheme, i.e. every other line rhymes. Tisbea’s speech above is an example. Spanish is a great language for loooooong romances because so many words rhyme! (The assonance helps.) In the play, I counted:

- 3 romances with a-a rhymes;

- 2 each with e-a and o-o rhymes;

- 1 each with o-a (above), i-a, and a-e rhymes.

- Acts II and III each contain a sequence of octavas reales: eight lines of eleven syllables each, with an ABABABCC rhyming pattern.

- Act II contains one sequence, and Act III two, of quintillas: five lines of eight syllables each. Amazingly, Tirso de Molina added an additional layer of structure by varying his quintillas‘ rhyming patterns. The quintillas in Act II alternate between ABBAA and AABBA, while those in the Act III sequences are all ABABA.

- Act I has a sequence of décimas: ten eight-syllable lines with a complex consonant rhyming pattern. The end of this sequence can be seen in the image above.

- Act III has a sequence of sextillas: six alternating lines of seven and eleven syllables (7-11-7-11-7-11) with consonant ABABABCC rhyme.

The rhyming complexity increases as the play progresses. Act I contains three patterns: redondillas, romances, and décimas. Act II contains four: redondillas, romances, octavas reales, and quintillas. And Act III contains five: redondillas, romances, quintillas, sextillas, and octavas reales. What a tour de force!

I read the play a first time for its language and rhyming, and a second time to focus on its plot and characters. On the second read-through it became clear that although Don Juan was a lecher, his uncle was equally evil in his own way. He was a reprehensible enabler, helping Don Juan escape and lying to cover his tracks. The women in the play were uniformly admirable, and also strong, once they’d realized they’d been conned. (This cast of characters inevitably reminded me of today’s politics.)

As you can imagine, after so much preparation I was excited to finally see the play. The performance I saw was at Teatro de la Comedia, Madrid’s theater for classical theater. (See my “Bad Spanish” post about their tickets, and also the YouTube clip below.) It was an excellent production! I found Don Juan himself incredibly sexy — I could see why so many women fell for him — but in the scene where his father appears, he becomes sullen and quiet. The implication (for me) was that unresolved “Daddy issues” were at the heart of his neurosis. My favorite scene, Tisbea’s mad scene after Don Juan betrays her, was powerful. It was a real treat.

Surprisingly, after I’d worked so hard to get to know the rhyming schemes, they receded into the background once the play was “live”. The lines just sounded like beautiful Spanish.

I left the theater with a strong urge to learn more about…Shakespeare! Having never taken a Shakespeare course in college, I feel guilty that I now know more about Tirso de Molina than our greatest English playwright.

Viggo Mortensen, “el argentino”

I have Arturo Pérez-Reverte’s Capitán Alatriste books on my mind these days because El Ministerio del Tiempo, the Spanish TV show I’m currently enjoying on Netflix, has a running joke about a time-traveler from the 1500s (played by Nacho Fresneda) who resembles Pérez-Reverte’s swashbuckling hero.

The Alatriste doppelganger specifically reminded me of an amusing conversation I had a few years ago with Lorena, a friendly Mexican woman who used to have a coffee kiosk near my train station. I frequently picked up a cup of coffee there and, naturally, would also enjoy a chat in Spanish.

One morning I happened to have the first volume of the Alatriste series with me when I picked up my coffee. I showed it to Lorena and she instantly recognized the handsome man on the cover. “Es el argentino,” she said.

This tickled my funny bone since she was referring to Viggo Mortensen, who played Alatriste in a movie based on the series, and who is actually Danish-American. Mortensen lived in Argentina when he was a young boy, returning with his American mother to the United States at age 11. It’s impressive that he’s held onto his Spanish…and his Argentinian accent.

Coincidentally, my son Aaron just sent me this clip of Viggo Mortensen speaking six languages, including Spanish:

If you look on YouTube you will find similar videos of him speaking other numbers of languages. Wouldn’t it be great if all Americans were multilingual?

Even more coincidentally, I recently rewatched Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, starring Mortensen as Aragon. He was perfect for the role — and in a few scenes, speaks Elvish.

¡El Ministerio del Tiempo has arrived!

For months I’ve been hearing about El Ministerio del Tiempo, a popular science-fiction TV show from Spain. It has just come out on Netflix in the USA, and I’m in the middle of the first episode. It’s awesome!

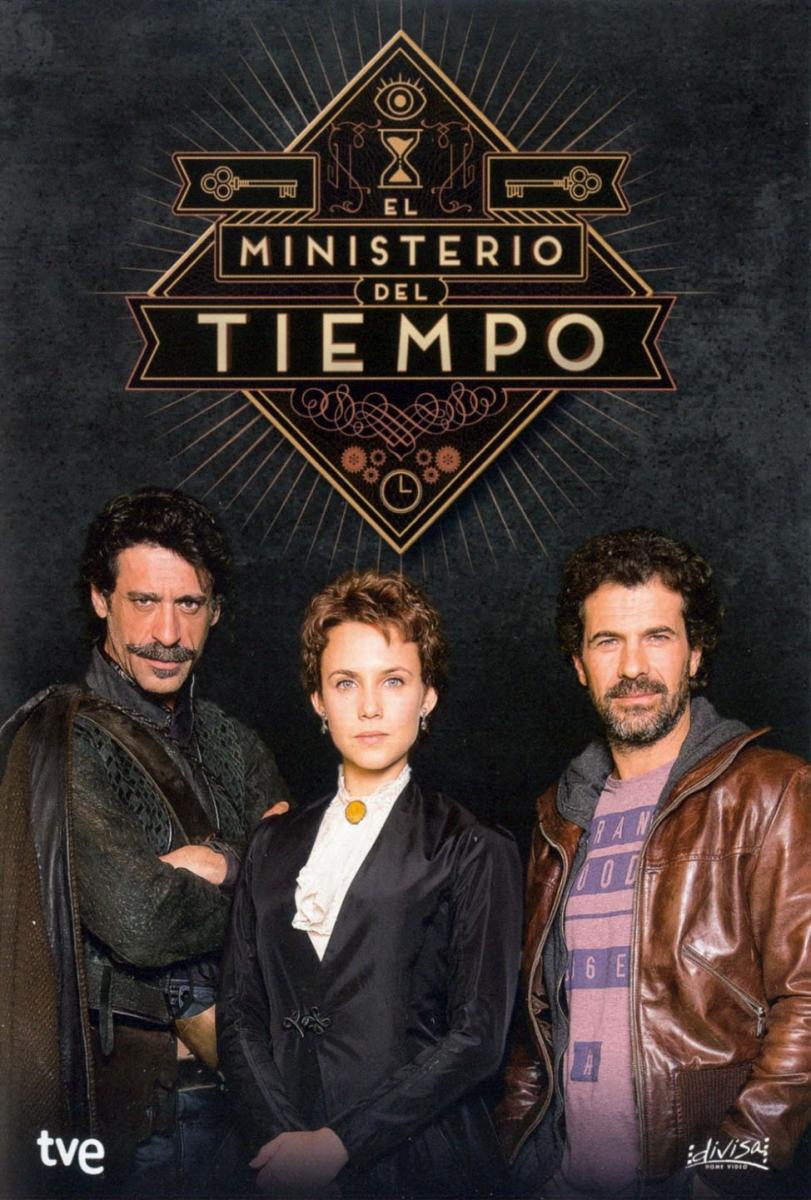

The show is about a secret Spanish government agency that controls a set of portals to Spain’s past. As best as I understand it so far, their mission is to stop nefarious time travelers from changing history. In the first episode they recruit new agents from the 1500s, 1800s, and the present (shown left to right in the picture). The show features a star turn by Diego Velázquez and multiple shout-outs to Arturo Pérez-Reverte‘s Capitán Alatriste.

As a linguist I am of course enjoying the older Spanish spoken in the 1500s scenes. And so far the plot and characters seem to be lots of fun.

Try it yourself!

An Academia for Ladino!

Regular readers of this blog already know that I’m a big fan of the Spanish language academy system, consisting of the Real Academia Española (RAE) and its 22 sister institutions, and collectively known as the Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española (ASALE).

I now have a new reason to love the Academia: the institution now expects to add a new sister academy, based in Israel, that is devoted to Ladino. Also known as Judeo-Spanish, or judeoespañol, Ladino is the language of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 and their descendants. Once spoken by hundreds of thousands of Jews around the Mediterranean, especially in Turkey, the language is now in danger of extinction. Unlike Yiddish, its German-based counterpart, which is still spoken as a first language by Hasidic communities in Israel and the United States, Ladino lacks fresh native speakers, and its older speakers are dying out.

A language academy for Ladino wouldn’t save the language, but it would help to conserve, study, and honor it.

According to an article in El Cultural, the RAE/ASALE has approved the formation of the Academy and has passed the bureaucratic baton to the State of Israel. Once Israel recognizes the Academy, it can then formally apply for membership in ASALE. It is hoped that this will take place by the next ASALE convention in 2019.

Very exciting!

Spanish language Nobel Prizes in literature

Every Spanish speaker can be rightly proud that “our” language is so international. It is an official language in twenty-one countries in North, Central, and South America, Europe, and Africa. The Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española provides oversight and stability while respecting dialectal differences.

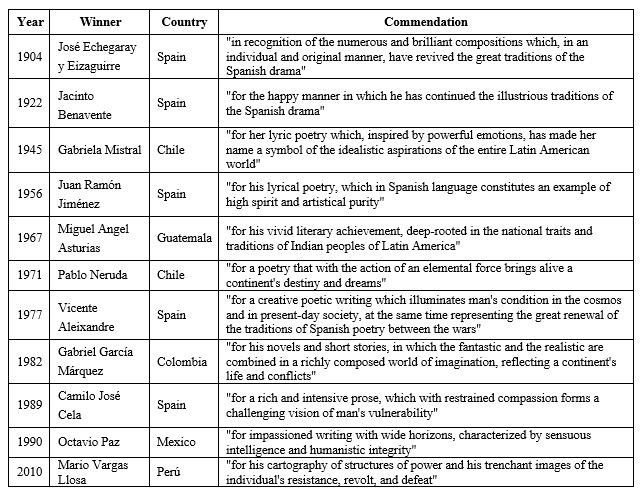

Another measure of the success of Spanish as an international language is the fact that Spanish speakers from four continents — Europe and the three Americas — have won Nobel Prizes in Literature. The chart below summarizes this achievement. The commendations are from the “Official Website of the Nobel Prize”.