I recently returned from a short visit to Italy with my husband. It was our third time there together. We spent one day in Milan, three in Florence, and four in Bologna, including a day trip to Ravenna to see the mosaics. My mother used to tell me about the mosaics, so I had her very much in my thoughts while we were there. It was the best day of the trip.

The first time we went to Italy, I worked through the first 100 or so pages of a standard Italian grammar workbook on the plane ride over. (It’s hard for me to sleep on an airplane, so I decided to use the time productively.) Given my Spanish, my French, and a year of college Latin, I found Italian easy to pick up. I managed to have some respectable conversations with hotel receptionists and restaurant servers. This time, I worked through Language Transfer’s Introduction to Italian course, which I recommend 100%! I also bought a short grammar reference book and an adorable book of short Italian stories for beginners, which I devoured. My favorite story was about a lonely yellow sock with a green stripe whose owner matches him with a lonely green sock with a yellow stripe, and wears them all over the world. This book was a lot of fun.

What struck me most about Italian the second time around was the similarity between its past tense and that of French. Like French, Italian has mostly abandoned the simple past (like I ate) in favor of the periphrastic past (like I have eaten), a transformation that may be underway with Spanish in Spain. Also, both Italian and French use two different auxiliaries (‘to have’ and ‘to be’) to form the periphrastic past tense, and the past participle (like eaten in I have eaten) agrees with the verb’s subject or object in a rule-governed but confusing way.

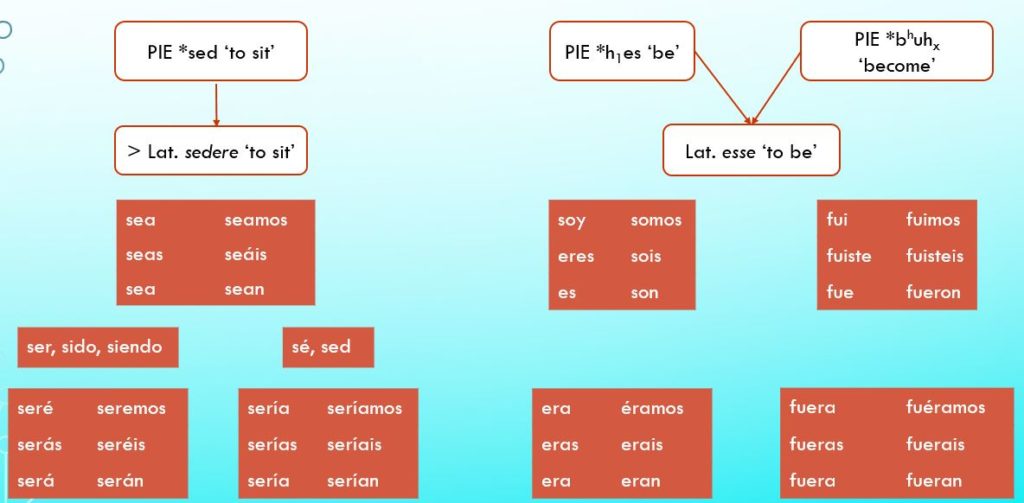

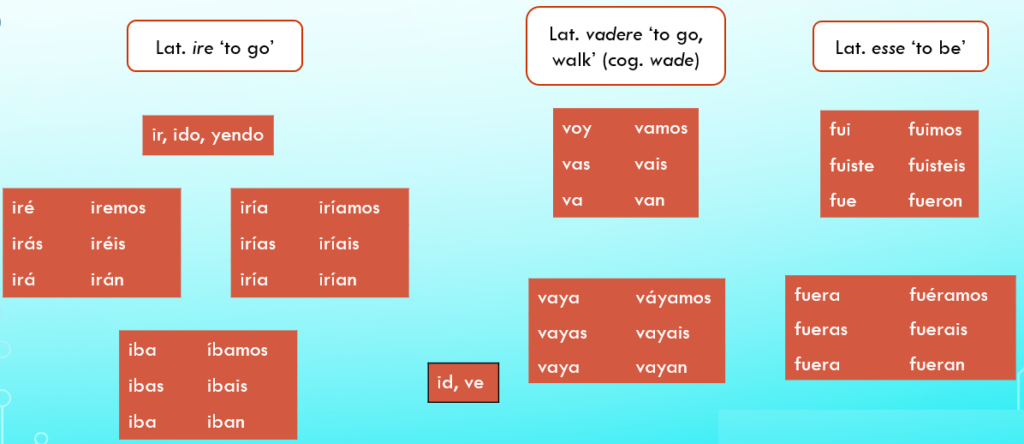

I also learned that Italian, unlike Spanish or French, does not have a periphrastic future tense. In Spanish and French you can either use the future tense conjugation (e.g. comeré ‘I will eat’) or, as in English, use the verb ‘to go’ as an auxiliary (e.g. Voy a comer ‘I’m going to eat’). Catalan doesn’t have a periphrastic future either, and in fact uses the verb anar ‘to go’ to form a periphrastic past, e.g. va parlar ‘He/she spoke’ — literally, ‘he/she went and spoke’. This tells us that the use of ‘to go’ as a future auxiliary, which Spanish and English speakers take for granted, must not have been uniformly present in Vulgar Latin.

Like other Spanish speakers (I suppose), I found that Spanish occasionally tripped me up when I was trying to speak Italian. For example, in Spanish andar and caminar both mean ‘to walk,’ but in Italian andare means ‘to go.’ As another example, I kept confusing Italian cinque ‘five’ with Spanish quince ‘fifteen’. But overall, Spanish was more of a help than a hindrance.

I did get to speak some Spanish during our trip, for example with a couple from Colombia who were staying at our hotel in Bologna. It was such a pleasure to slip back into my comfort zone! I also took advantage of our presence in the European Union to finally purchase a jigsaw puzzle of Gaudi’s “El Capricho” house in Comillas, Spain that I had been coveting since 2019, thereby saving $35 on postage.

During this visit, my attempts at conversation were less successful than previously, with people I spoke with switching to English. I can think of several possible explanations for this:

- Perhaps this year’s crash course in Italian wasn’t as successful as previous attempts. I am several years older, after all. But I sincerely believe that my Italian is pretty good, given that I don’t actually speak Italian! I’d rather find an alternative explanation. So…

- Since we were staying at more luxurious hotels this time around, perhaps their staff are proudly bilingual, and trained to reply to clients in their own language.

- It’s also possible that given the current influx in American tourists in Italy, Italian hospitality workers in general are primed to speak English

At any rate, now that I’m home Italian is going on the back burner — until the next viaggio.