Regular readers of this blog know that I’m obsessed with the two different versions of the Spanish imperfect subjunctive. This is the verb form that you see in sentences like Quería que Miguel estudiara más ‘I wanted Michael to study more’. This -ra form is more common in general, but it’s equally acceptable to use forms with -se, in this case estudiase. The -ra and –se imperfect subjunctives are both understood around the Spanish-speaking world; their relative frequency varies according to dialect.

Regular readers of this blog know that I’m obsessed with the two different versions of the Spanish imperfect subjunctive. This is the verb form that you see in sentences like Quería que Miguel estudiara más ‘I wanted Michael to study more’. This -ra form is more common in general, but it’s equally acceptable to use forms with -se, in this case estudiase. The -ra and –se imperfect subjunctives are both understood around the Spanish-speaking world; their relative frequency varies according to dialect.

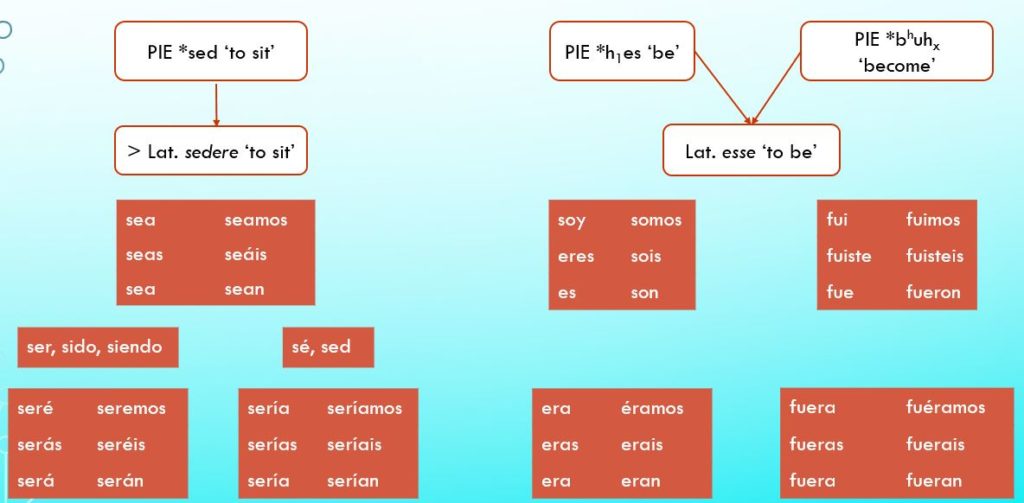

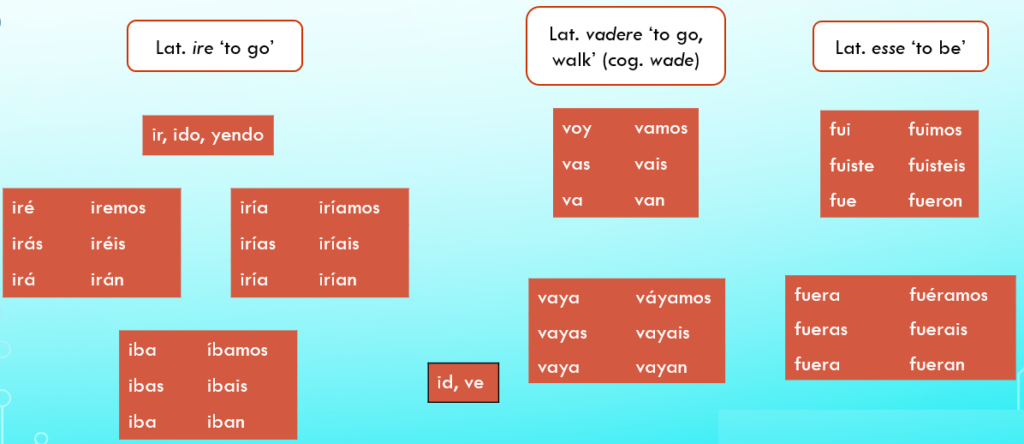

This aspect of Spanish is interesting for two different reasons. First of all, it’s extraordinarily unusual for a language to have such “twin” forms in the heart of their grammar. I haven’t been able to find a single other example after searching the linguistics literature for over five years. Second, neither of these forms is a direct descendant of Latin’s own imperfect subjunctive. Rather, two other existing conjugations were “repurposed” as imperfect subjunctives: the -se version in Old Spanish, and the -ra form more recently, in the time of Cervantes.

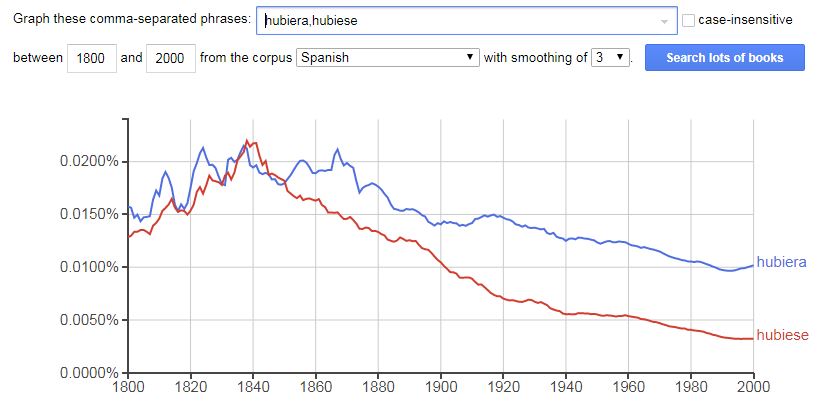

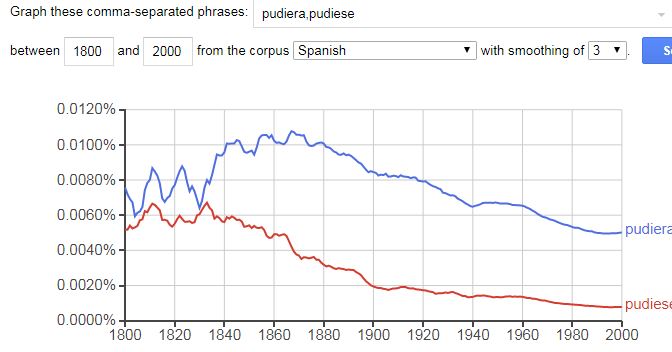

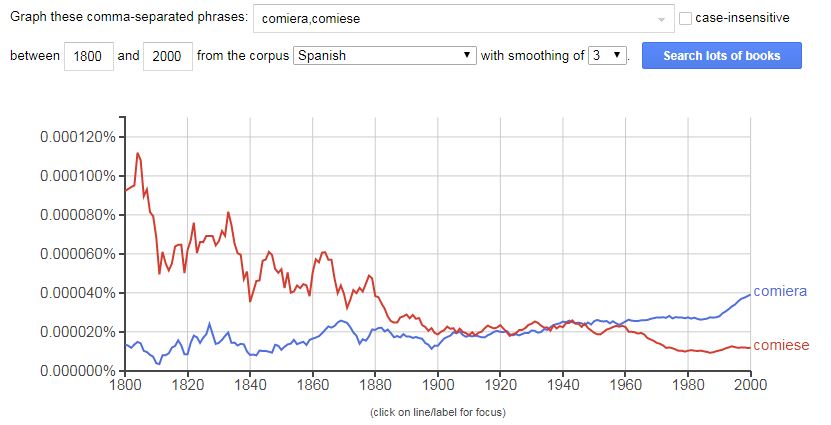

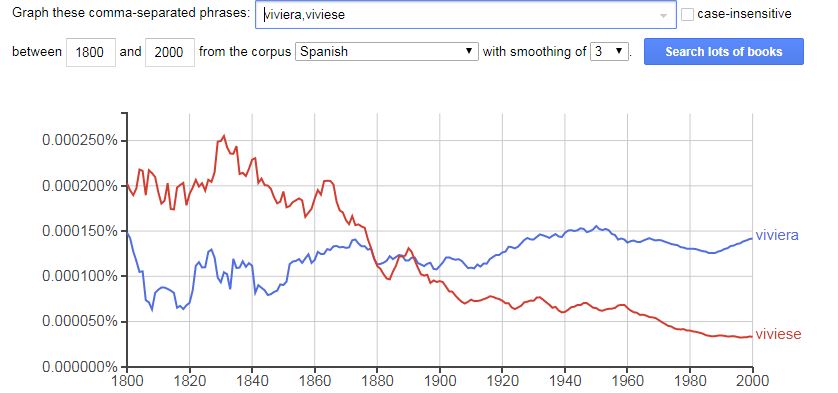

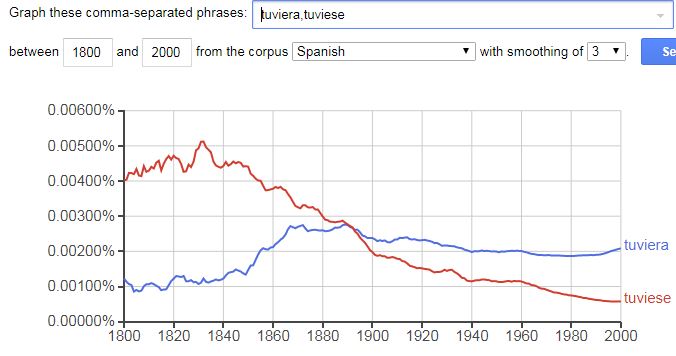

Google Books’ “Ngram Viewer” provides an easy way to see the newer -ra subjunctives overtaking the older -se forms. Google has digitized over 25 million books in English, Spanish, and other languages. Their free “Ngram Viewer” tool analyzes word frequencies in this corpus, making it easy to compare frequencies of two or more words over time.

In this post I’ve reproduced six graphs comparing -ra and -se subjunctive frequencies over the last two centuries. The first three graphs (one above, two below) show historical frequencies for the two forms of the imperfect subjunctive for the common irregulars tener, haber, and poder. The remaining three graphs show frequencies for the three regular verbs often used to illustrate Spanish’s -ar, -er, and -ir noun classes: hablar, comer, and vivir. In every case you can see the innovative -ar forms come from behind — or, less often, from parity — to overtake their -se twins. This happened earlier for the irregular verbs than the regulars; I don’t have a theory about why.

Keep in mind that written language is relatively conservative, so it’s safe to assume that -ar actually made its move somewhat earlier than shown in these graphs.