This semester I have been in the odd situation (for a Spanish teacher) of teaching the crucial topic of preterite vs. imperfect (e.g. hablé vs. hablaba) after a multi-year gap. For the last few years I have only been teaching our introductory course, but for this semester I requested an higher-level class, which begins with a review of the past tense before launching into the subjunctive. So here I am.

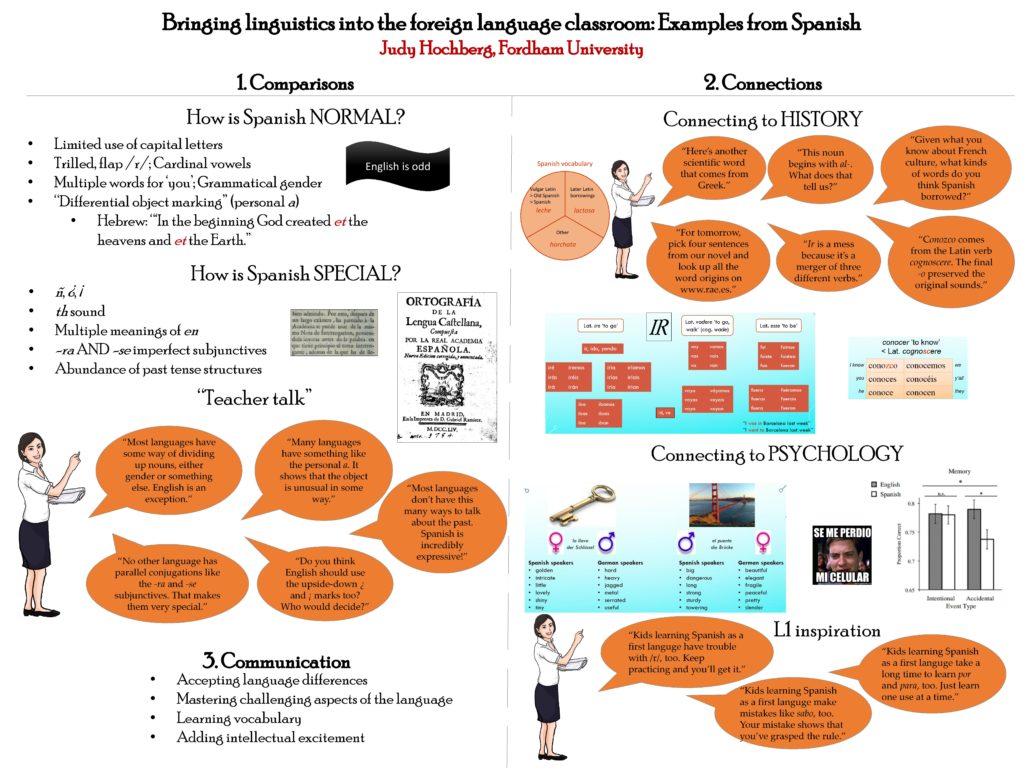

During this hiatus, Routledge published my second book, Bringing Linguistics into the Spanish Language Classroom: A Teacher’s Guide. This book obviously focuses on pedagogy, and comes with hundreds of PowerPoint slides that teachers can use in their classrooms. You can actually download these slides from the Routledge website without purchasing the book (click on “support materials”), but of course I recommend buying the book as well!

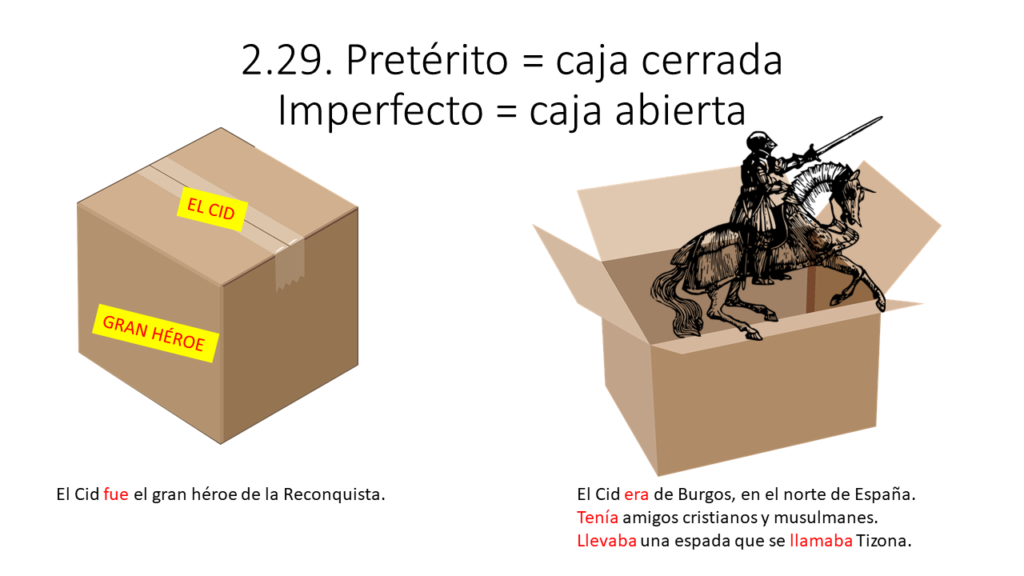

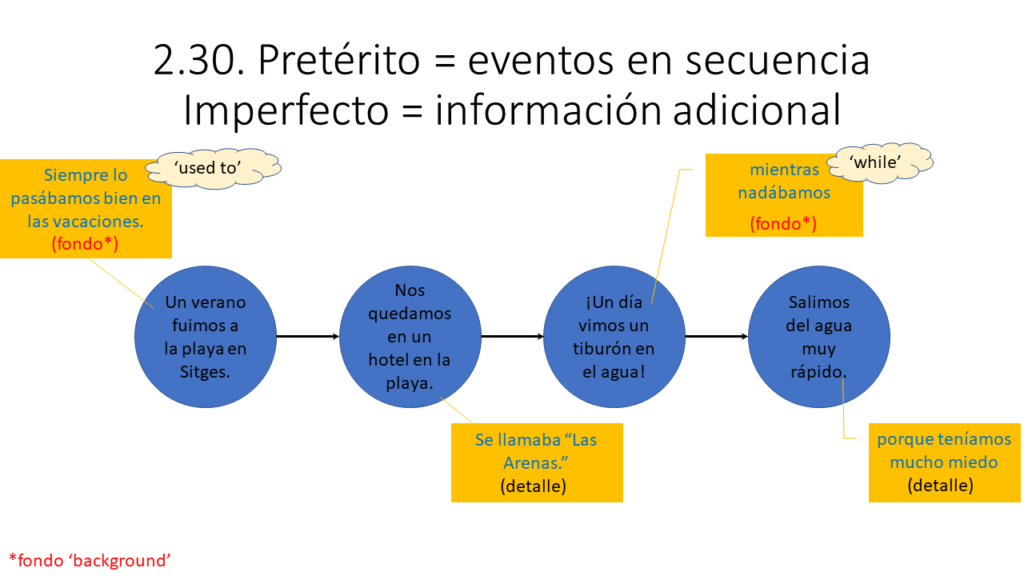

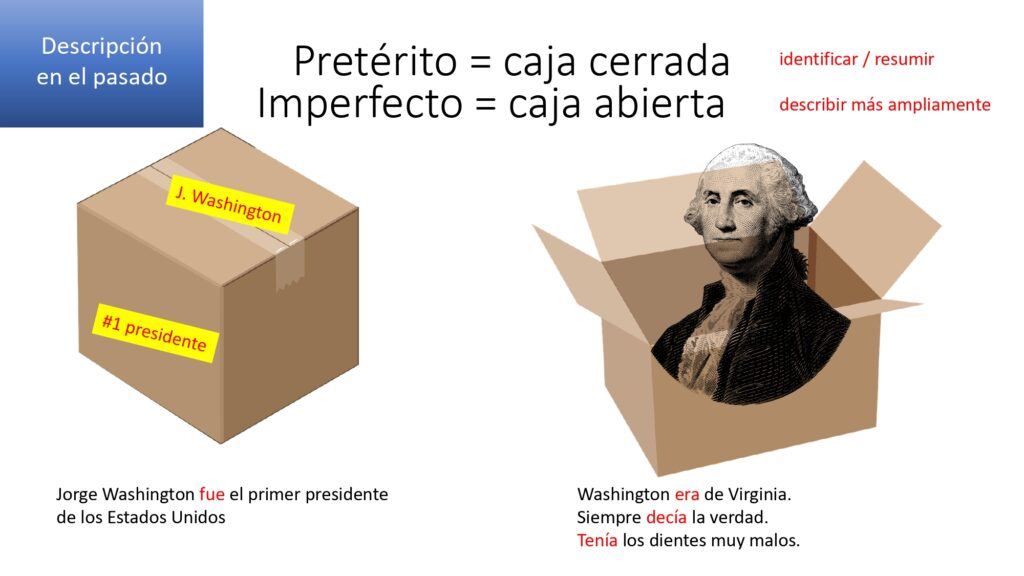

The book’s section on preterite and imperfect introduces two metaphors: beads on a string, and a closed versus open box. Here’s the relevant text from the book, followed by slides that illustrate the metaphors:

The distinction between completed and continuing events is simple in the abstract but elusive in practice. For this reason many teachers train their students to rely on various rules of thumb when deciding between preterite and imperfect. Some of these rules concern the type of past occurrence; for example, students may learn to use the preterite to describe beginnings and endings (e.g. empezó and terminó) and the imperfect to describe the weather (e.g. llovía). Other rules focus on contextual clues, such as specific timeframes for the preterite (e.g. todo el día) and mientras for the imperfect. While helpful, the former rules are fallible (e.g. El orador empezaba a hablar cuando el micrófono falló; Ayer llovió durante tres horas) and the latter are often absent in actual speech or writing. Sooner or later students have to grapple with the aspectual difference itself.

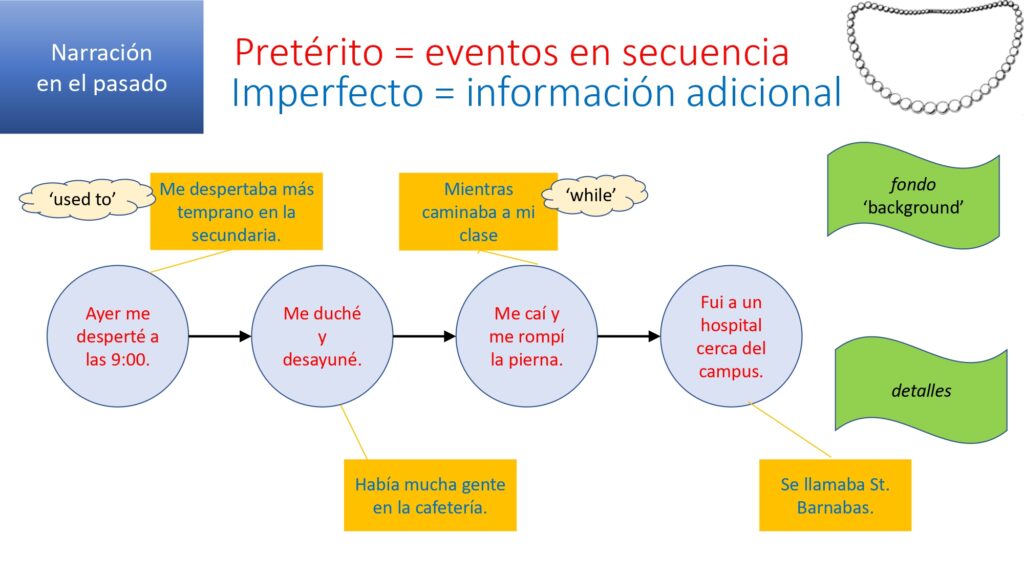

The visual metaphors in Slides 2.29 and 2.30 can help. Slide 2.29 depicts the preterite as a closed box containing a past occurrence (in this case the life of El Cid), and the imperfect as an open box that “unpacks” the occurrence, telling us more about it. This metaphor is particularly helpful when deciding between fue and era. Slide 2.30 depicts multiple preterite events as discrete and sequenceable, like beads on a string. This metaphor is particularly useful when teaching students to construct narratives. The animation in [the PowerPoint version of] Slide 2.30 shows how one can use the imperfect to add color to a bares-bones preterite narrative, an exercise described later in this section. Students may be interested in learning that children usually acquire the two tenses in this same order, i.e. preterite before imperfect (Slide 5.19).

In our first class meeting of the semester, I embedded the slides from my book into a mini-lesson in which I:

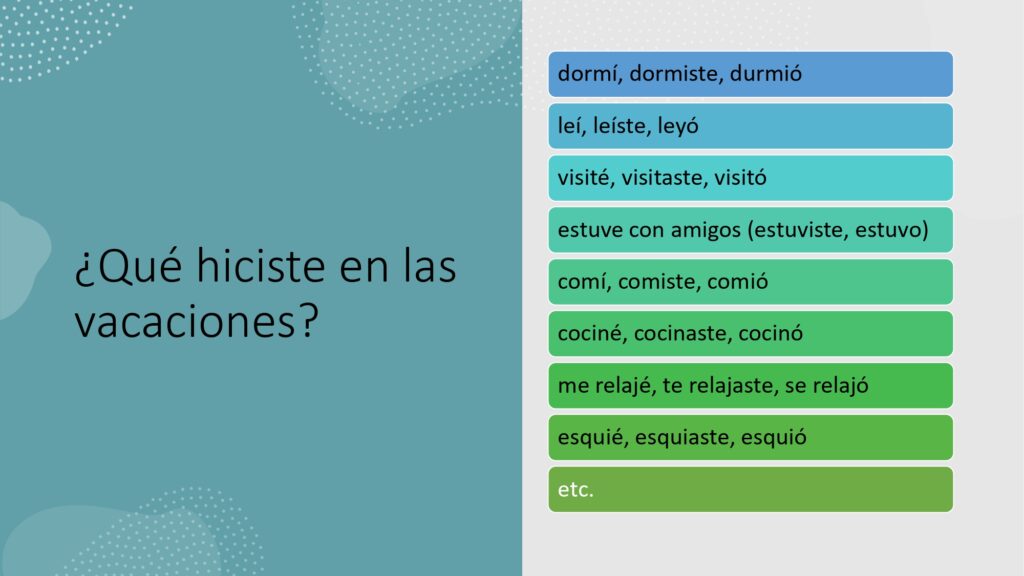

- elicited some preterites during a class-opening chat;

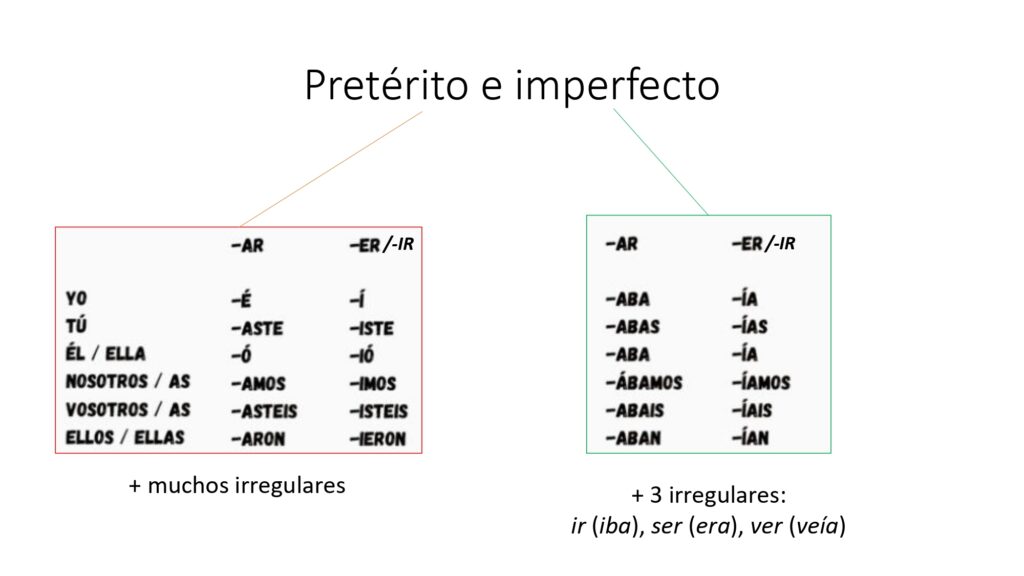

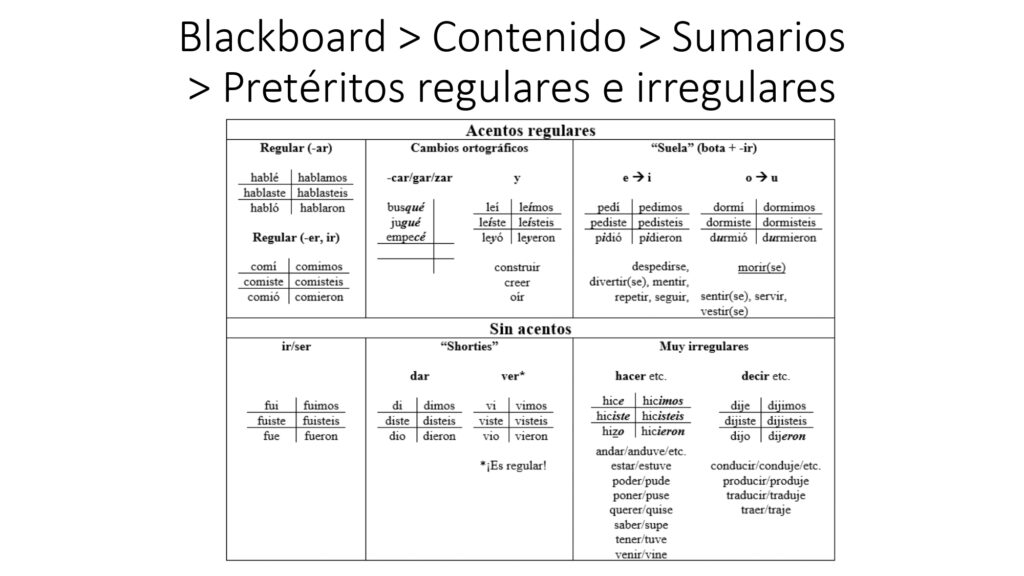

- briefly reviewed the two conjugations;

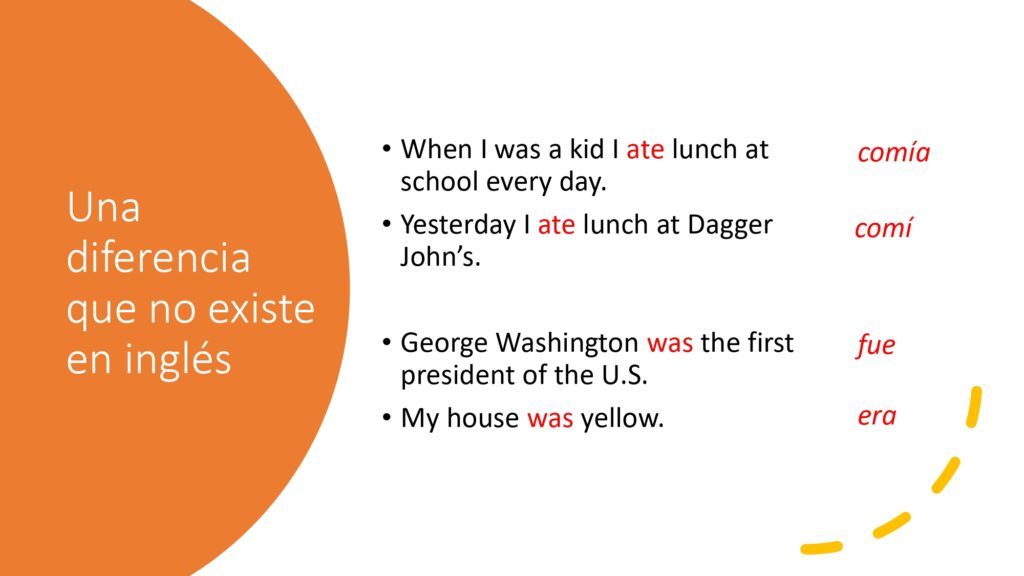

- contrasted Spanish with English to explain the challenge of this topic;

- presented the two metaphors at a high level;

- walked through the “beads in a string” (un collar de perlas) animation in an updated version of my book’s slide 2.30;

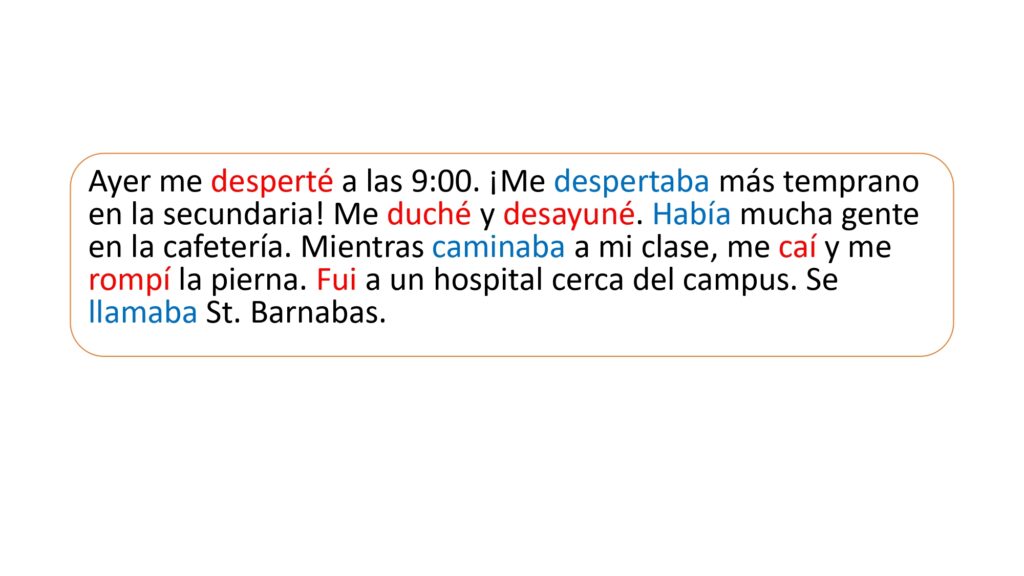

- showed the result: a natural switching back-and-forth between the two tenses;

- presented the open vs. closed box metaphor (again, with an updated version of the published slide);

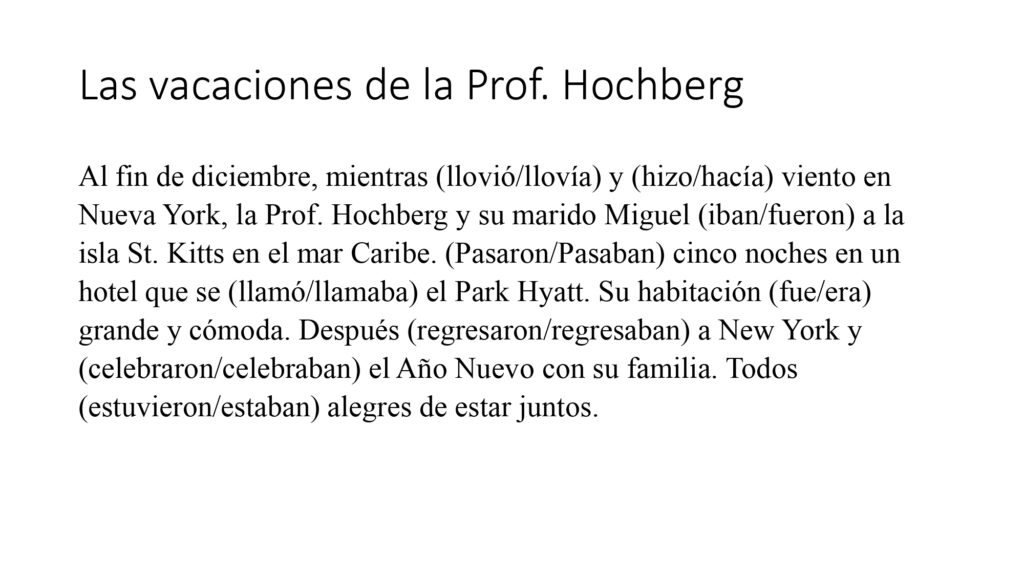

- had students choose between preterite and imperfect in a simple passage.

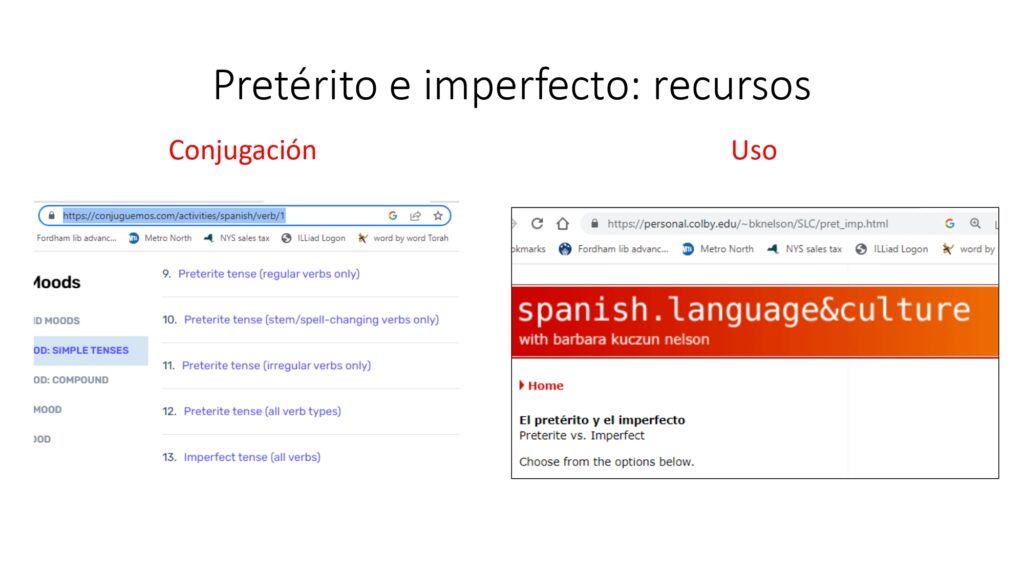

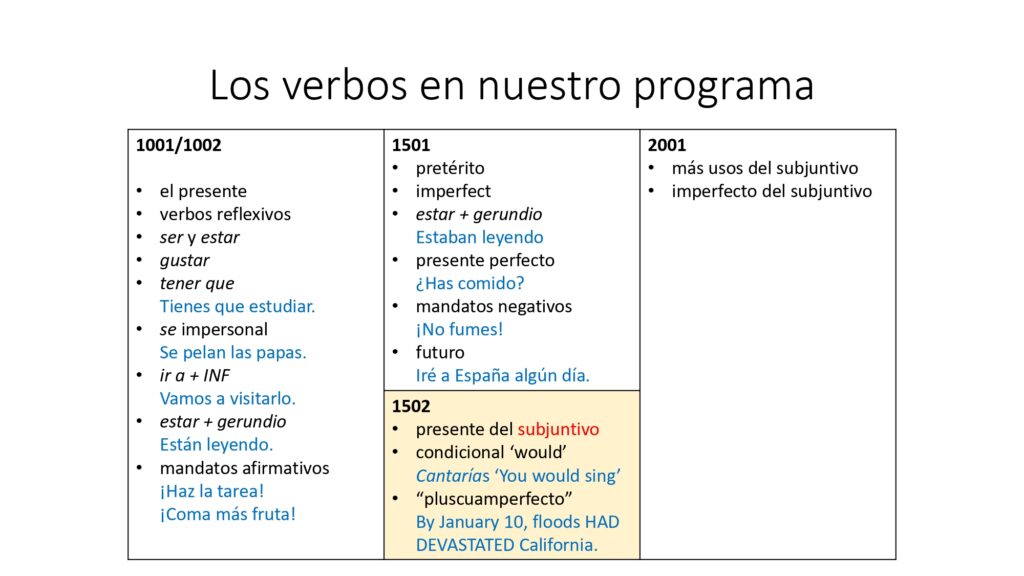

I also presented some favorite resources for students to pursue on their own, including my own divide-and-conquer, one-page summary of the preterite conjugation. A final slide showed them where we were, verb-wise, in our Spanish language sequence.

In the next class, I reviewed the use of preterite and imperfect via a group effort to tell the Cinderella story, then had pairs of students write short and simple narratives of their own, giving them a choice of well-known stories from Noah’s Ark to Avatar. Each pair received three pink index cards on which to write three key events on the preterite, and then white index cards, as needed, for them to add background information and details in the imperfect.

I had never had the chance to classroom-test these specific slides from my book, so it was exciting to finally put them into practice, especially since my students were receptive to the two metaphors. They did a decent job with their narratives; I’ll see how what they learned holds up as the semester rolls on.