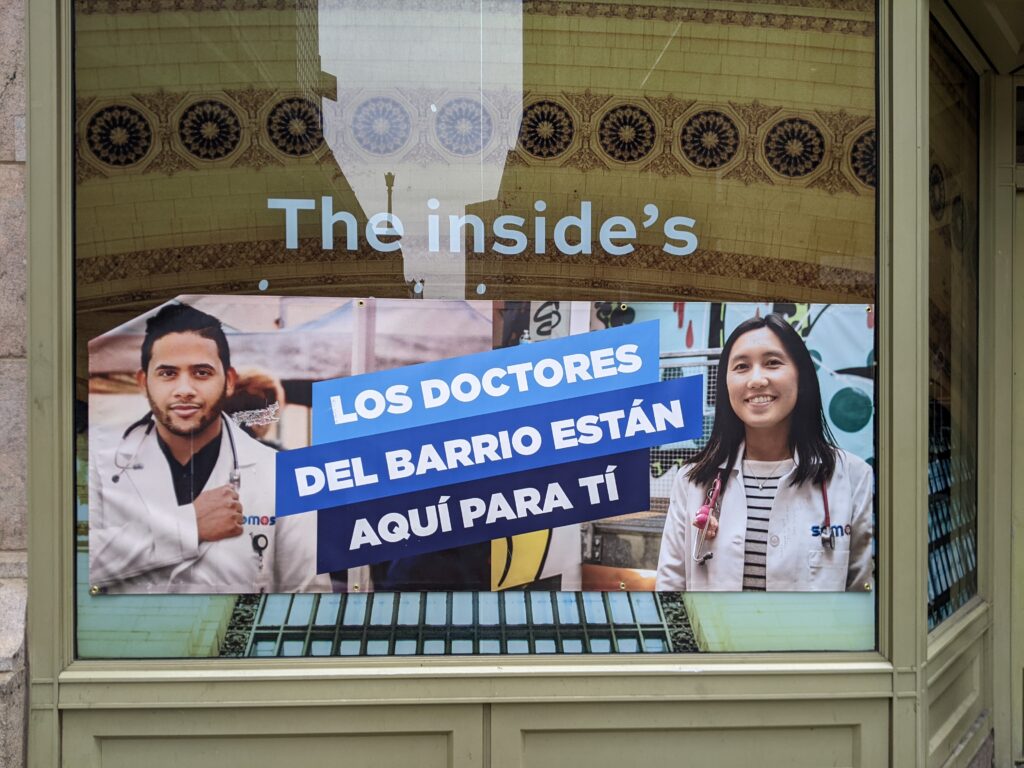

Last year I posted about bad Spanish in a storefront advertisement for a public health program in New York City. I called that post a “guilty conscience edition” because I felt bad criticizing the program. But I think it’s important to call out bad Spanish wherever it appears.

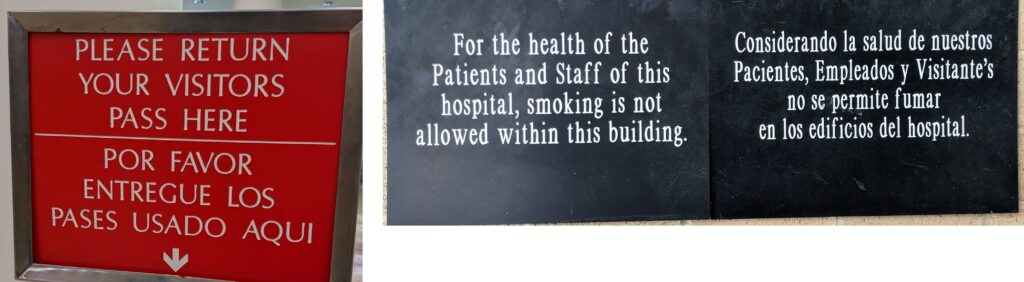

On Monday I had occasion to visit one of the city’s great medical establishments, formerly known as Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, but now as NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. In the Milstein Building, where I went for breakfast, I spotted two problematic signs. They are shown below “as is” and digitally revised.

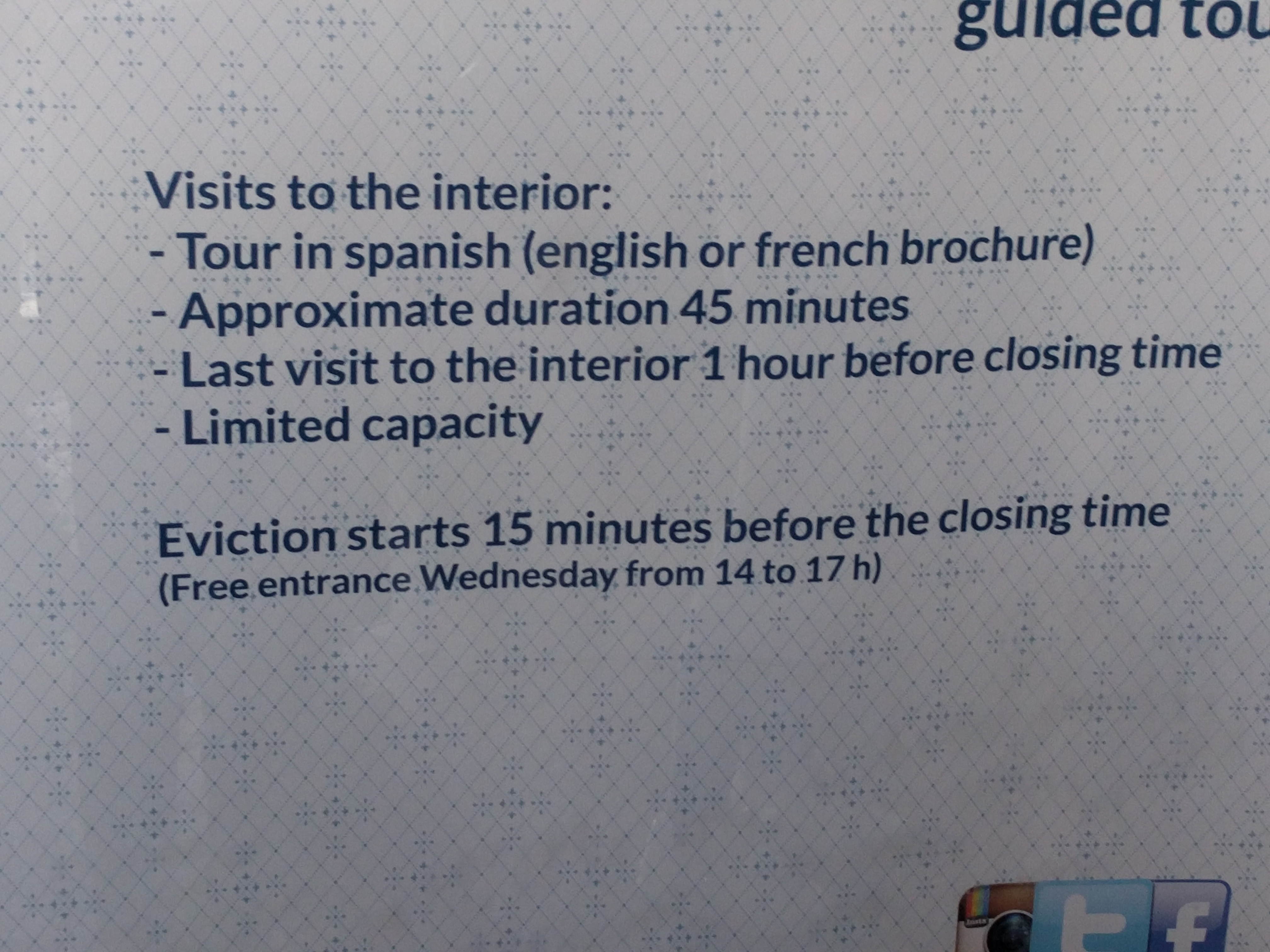

Bad Spanish at the Milstein Hospital Building

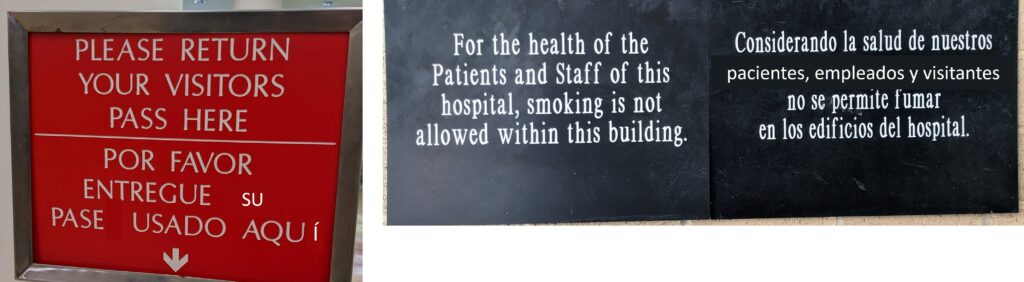

My suggested revision

The first sign is inside the lobby, on the way out. My suggested revision resolves the current disagreement between plural pases and singular usado in favor of the singular (in line with singular entregue), and restores the very necessary accent mark on aquí. (Accent marks are required on both lower- and upper-case letters.) I also followed the English version in using possessive su instead of the definite article el or los.

The second sign is on the outside wall of the building, near the front exit. It’s a doozy! My revision eliminates the unnecessary and un-Spanish capital letters on pacientes, empleados, and visitantes. More importantly, it removes the offensive apostrophe in visitantes. Like English, Spanish doesn’t form plurals with ’s. In fact, apostrophes are only used in written Spanish to represent colloquial shortenings like pa’ for para.

I’m grateful to Columbia Presbyterian for seeking to accommodate their Spanish-speaking staff and visitors, but wish they had consulted with a trained Spanish speaker/speller before having these signs made.