Georgina Margan, a reader and professional translator from Tucson, Arizona, emailed me to give Trader Joe’s “a pat on the back for their Chicken Asada“, the subject of a “Bad Spanish” post on my blog. Whereas I complained that the product should be called Chicken Asado because pollo ‘chicken’ is masculine, she made the point that ‘chicken’ can also be feminine — and, in fact, that the feminine gender rules when chickens are plural:

The agreement between chicken and asada is correct because chicken means gallina (hen), not only pollo. You see, when chicks are born it’s next to impossible to tell females and males apart…unless you cut them open. Only when they grow up the difference between gallinas (feminine) and pollos (masculine) becomes evident. Pollos turn into gallos (roosters), if they are given the time. When both sexes are together in a flock, they are collectively referred to as las gallinas. This is one of the very, very few instances where a group of both sexes is referred to using the feminine noun.

Wordreference.com and the Real Academia certainly back up Gina’s point about the feminine collective plural gallinas. The former lists three earthy refranes (‘proverbs’):

- acostarse con las gallinas ‘to go to bed early’ (lit. ‘to go to bed with the chickens’)

- ¡hasta que meen las gallinas! ‘when pigs fly’ (lit. ‘when chickens piss’)

- Las gallinas de arriba ensucian a las de abajo ‘the underdog always suffers’ (lit. ‘the chickens on top poop on the chickens below’)

The Real Academia repeats the first two refranes and also references cólera de las gallinas (‘fowl cholera’), a nasty disease which fortunately hasn’t crossed over to humans. Yet.

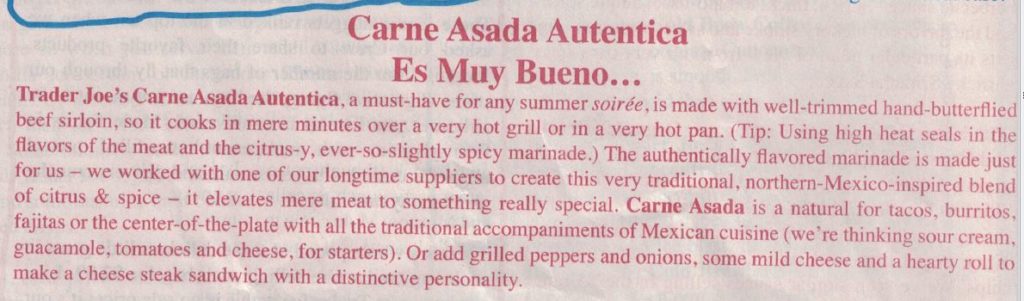

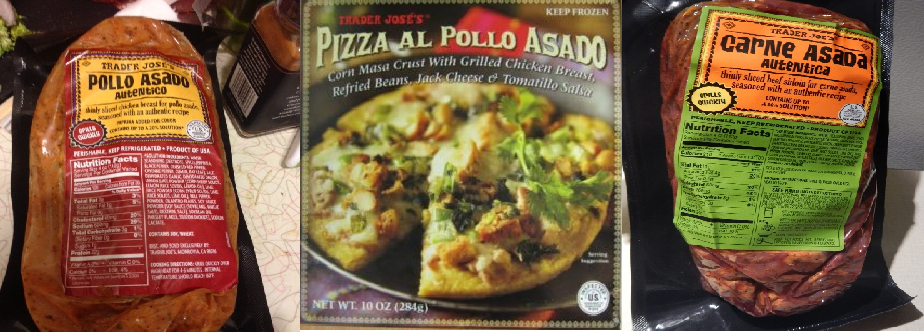

However, I still think it would be better for TJ to call this product Chicken Asado because the company clearly sees chickens as pollo, not gallina, as shown in the related product names Pollo Asado and Pizza al Pollo Asado.

One of these days I should actually sample one of these products!