Note: this post is intended for Spanish verb fiends only! Others read at your peril!

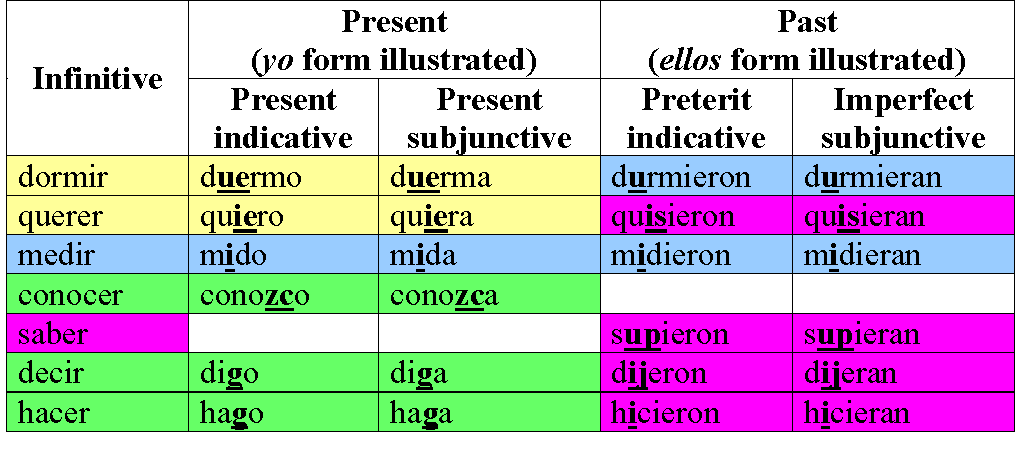

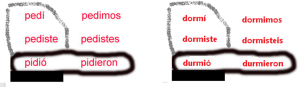

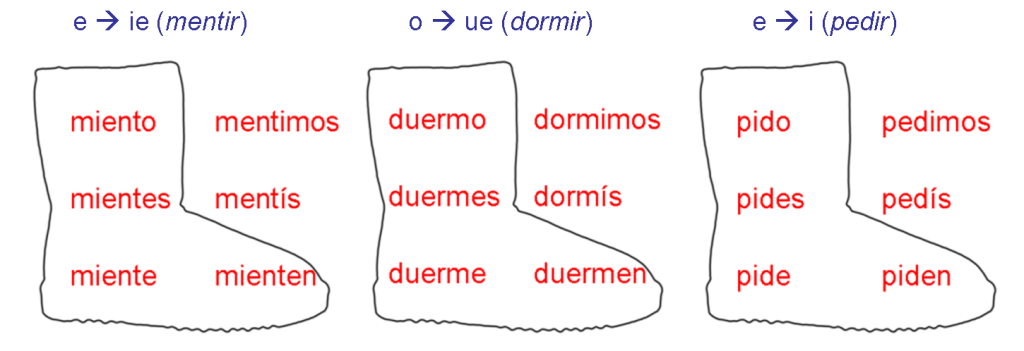

The Spanish verb system is riddled with irregular verbs, but at least they fall into discernible patterns. For example, verbs that end in -ir and have a stem change in the present tense are also irregular in the preterite, imperfect subjunctive, and gerund. These fall into three groups:

- o/ue/u

* Example: dormir ‘to sleep’, duermo ‘I sleep’, durmió ‘he slept’, durmiendo ‘sleeping’ - e/ie/i

* Example: sentir ‘to feel’, siento ‘I feel’, sintió ‘he felt’, sintiendo ‘feeling’ - e/i/i

* Example: servir ‘to serve’, sirvo ‘I serve’, sirvió ‘he served’, sirviendo ‘serving’

The silver lining to this cloud of complexity is that it is, at least, predictable. As implied above, there are no exceptions to this pattern, i.e. -ir verbs with a stem change in the present tense that are regular in the preterite and the gerund.

Or are there?

To my horror, and great interest, I learned just today of two exceptions: cernir ‘to sift’ and hendir ‘to slit open’. Despite their present-tense stem changes (cierno, hiendo, and so on) they are regular in the preterite (cernió, cernieron, hendió, hendieron), imperfect subjunctive (cerniera, hendiera, etc.), and gerund (cerniendo, hendiendo). You can see the full conjugations here and here.

Discernir and concernir share the same irregularity as cernir, as you might expect. (This is why I made sure to use the English cognate discernible at the beginning of this post. 😉 )

Not surprisingly, the Real Academia’s Diccionario panhispánico de dudas contains warnings against forms such as hindió, hindieron, and cirniendo.

Fortunately, there is a logical explanation for these irregular irregulars: cernir and hendir are variants of the -er verbs cerner and hender, from Latin cernĕre and findĕre. In other words, they are innovative -ir verbs that still think they are -er‘s with respect to this irregular pattern. If I can attempt a wacky analogy, they’re akin to someone who dyed their hair but red still lacks the freckles that a natural redhead would have.

Just for fun, I used the Google ngram viewer to trace the history of cerner, cernir, hender, and hendir. None of these verbs is very common, but the -ir variants have definitely caught up to the older -er forms over the last two hundred years or so, and, in fact, have managed to surpass them.

(Post continues after graphic.)

If you look at a shorter time period, you can clearly see hender nose-diving to fall just behind hendir. It’s pretty cool.