I can remember the exact moment when Spanish utterly and permanently captivated me. I was fifteen years old and in my fourth year as a Spanish student. Our class had wrapped up the basic tenses and the present subjunctive, and was ready to launch into the imperfect subjunctive. Our teacher explained to us that this tense was based on the pretérito and incorporated all of its irregulars.

This struck me as laugh-out-loud funny. We had already learned that the present subjunctive inherited all the idiosyncrasies of the normal present tense, including the ones that only show up in the yo form (the -zco and -go types). But the preterit is even thornier. It seemed bizarre beyond belief that the subjunctive should adopt the most problematic elements of both these tenses.

As a student, it amused me to imagine that a twisted “Spanish committee” (perhaps a branch of the Spanish Inquisition?) had designed the subjunctive. (My little PowerPoint below depicts this scenario.) As a teacher, I now like to tell my students that the present subjunctive is God’s way of getting them to review the irregular verbs that they’d studied weeks, months, or even years ago. I figure that teaching at a Jesuit university authorizes me to invoke God in the classroom.

In fact, the many irregulars of the subjunctive are neither a cosmic joke, an evil machination, nor an act of God. They’re simply a coincidence. The present and imperfect subjunctive happened to follow the same evolutionary paths as several distinct categories of irregular verbs in the present and pretérito indicative.

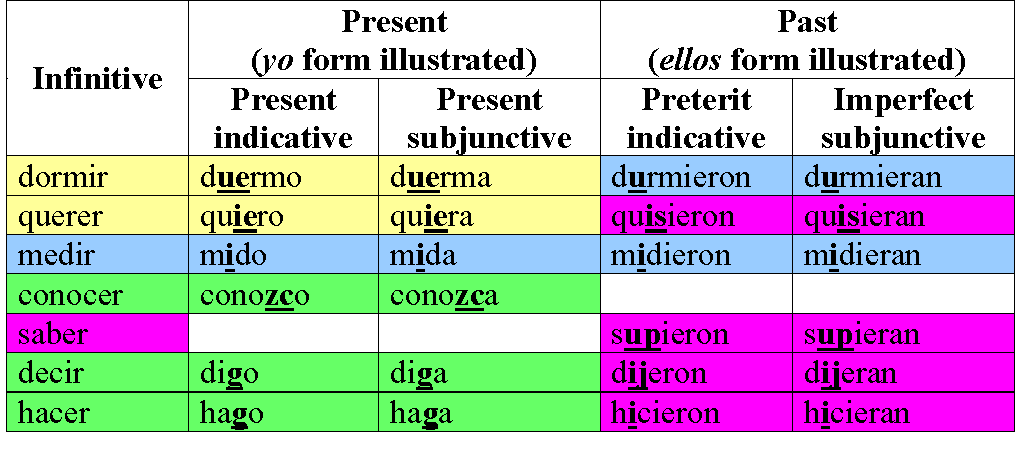

Consider the examples of irregular verbs shown in the table below, color-coded for your convenience.

The “boot” verbs, in yellow, are irregular in the present tense because of a language-wide process that changed stressed /o/ to /ue/ and stressed /e/ to /ie/. The corresponding present subjunctives have the same vowels and the same stress pattern, and therefore the same irregularity.

The -ir “sole” verbs, in blue, are irregular in the present and the pretérito because of another general process: the raising of /e/ to /i/ and /o/ to /u/ before /j/ (the sound of English y). All Latin -ire present subjunctive endings, and the “sole” (3rd person) endings of the imperfect subjunctive, contained (or still contain) /j/, triggering the vowel change.

The -zco and -go irregulars of the present tense, in green, evolved because the –o ending of the yo form insulated it from changes that affected the other present tense forms and the infinitive. The subjunctive endings for these verbs begin with –a, which had the same insulating property.

Finally, the drastic stem-changing pretéritos, in magenta, descend from Latin’s “strong perfect” past tense forms. The imperfect subjunctive is based on Latin’s pluperfect tense, which had the same irregularities.

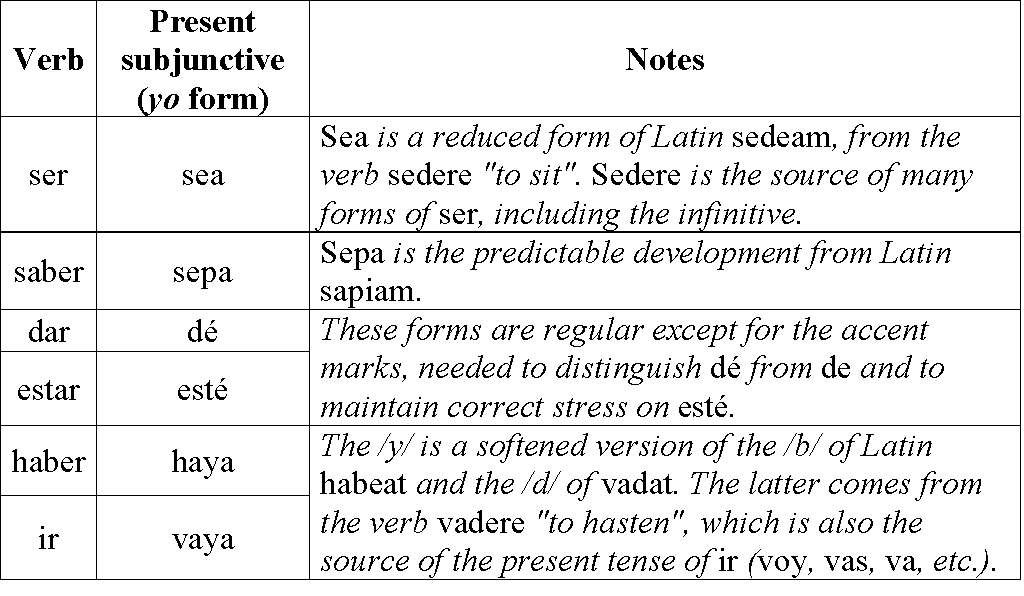

This leaves “only” the six additional irregulars of the present tense subjunctive. Their diverse origins are summarized below.

As always, if you want to learn more, the best source is Ralph Penny’s A History of the Spanish Language. But beware — nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!