At times like these, with death tolls continuing to mount in New York, where I live, and in Madrid, which I have visited so many times for learning and pleasure, it is reassuring to know that the Real Academic Española is on top of the situation — from a linguistic perspective, at least.

In a recent series of tweets, the RAE weighed in on both the gender and the proper capitalization of Covid-19. Covid-19 falls into the category of nouns that lack obvious gender because they don’t end in -o or -a. One frequent treatment of such nouns is for them to adopt the gender of their broader category. For example, I was always taught that catedral is feminine because it is a kind of church (la iglesia). Likewise, capital is masculine in the sense of money (el dinero) but feminine in the sense of city (la ciudad).

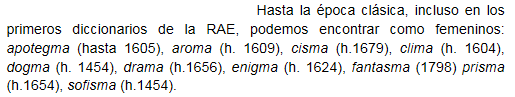

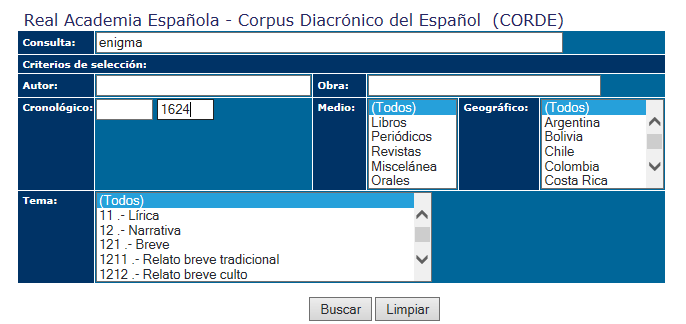

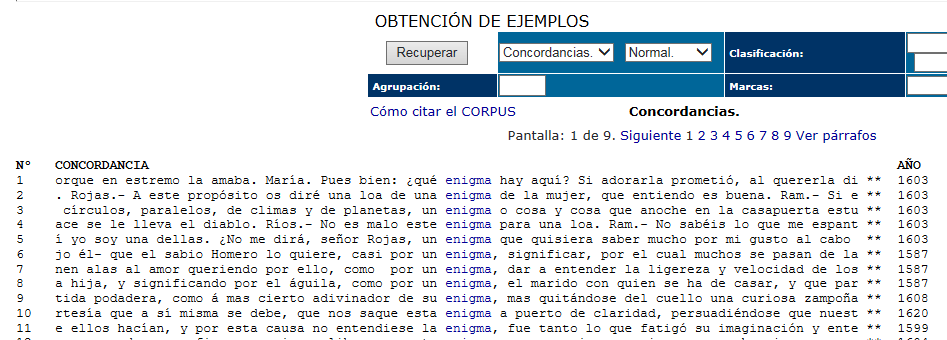

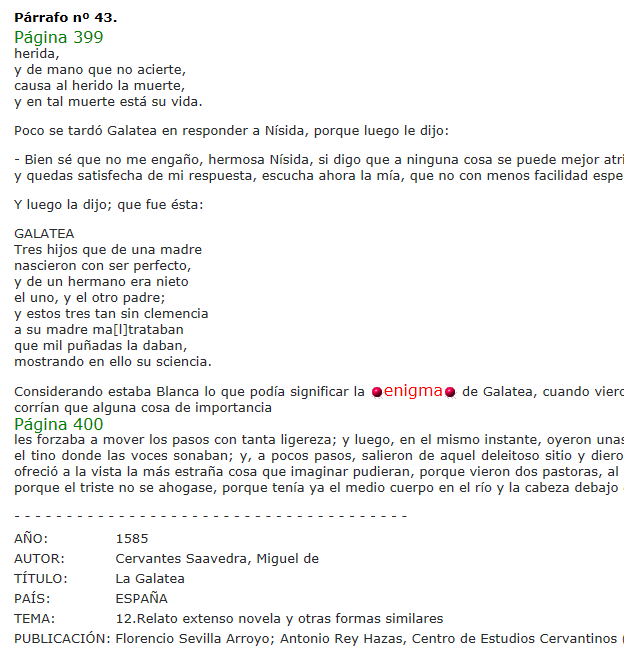

This practice can even make -a nouns masculine. This can be seen in words for masculine players of feminine instruments (el corneta ‘bugler’), masculine users of feminine tools (el espada ‘swordsman’), varieties of wine and liquor named after feminine regions of origen (el champaña, el rioja), since el vino and el licor are both masculine, and el caza ‘fighter plane,’ a type of avión (masculine).

According to this practice, the gender of Covid-19 depends on whether it is a virus or an illness, because el virus is masculine and la enfermedad is feminine. The RAE recommends the masculine gender, in keeping with other virus names such as el zika and el ébola (note that both end in -a), but says that feminine gender is also acceptable when focusing on the illness rather than the virus itself.

Moreover, the RAE’s tweets recommend the use of all-caps when writing the name of the virus (COVID-19), since it is “a recently created acronym,” but envisions switching to lower-case covid-19 if the disease becomes “a common disease name.” In other words, for the time being the appropriate treatment is all-caps with masculine gender, but time may lead to a switch to lower-case letters and feminine gender.

Now, if the RAE could only do something about the shortage of papel higiénico we would all be sitting pretty.