This post is about the eleventh and most recent book in Jordi Sierra i Fabra’s “Inspector Mascarell” series, Algunos días de noviembre, which I finished reading last night. I called this post “An imperfect novel” for two reasons. First, the book contains a fascinating use of the Spanish imperfect tense, which I’ll get to later. But also the novel itself, while enjoyable, struck me as imperfect because it added little to Sierra i Fabra’s serial depiction of life under a dictatorship.

The plots of the previous novels in this series have blurred together for me, but my impression is that they have all related to broad political themes. This is most obvious in the first novels, which take place just before and after Francisco Franco’s victory in the Spanish Civil War. Out of the later novels I remember one that involved an attempt to assassinate Franco, one that featured Civil War graves (or was it missing soldiers?), one about Communists, and so on.

In contrast, the plot of Algunos días de noviembre concerns a theatrical agent who receives threatening letters, and a murder that then ensues in his circle. I kept waiting for something to happen that would tie in this plot with Sierra i Fabra’s major themes. The mystery itself was enjoyable, and I ended up pushing on to the last chapter to find out what happened, but it never made sense that Mascarell, and not some other detective, would be pursuing this investigation.

Beyond this (for me) major problem, Algunos días has all the familiar and pleasurable plot elements of a Mascarell novel, which to this habitual reader feel as comfortable as slipping on a favorite pair of shoes: Mascarell’s traversal of Barcelona, his family (no spoilers!), his dislike of chatty cab drivers, his skill in interviewing suspects and other persons of interest, and his dogged pursual of the truth at any cost. You do learn something about the theatrical and cinematic scene in Barcelona in the early 1950s, thanks to Sierra i Fabra’s research in newspaper archives as described in an afterword.

One of these days I am going to reread these books while consulting a map of Barcelona. The novels have a strong sense of place but I am mostly reading them ‘blind’ beyond major landmarks such as Diagonal, a major street in the city, and the Tibidabo hill.

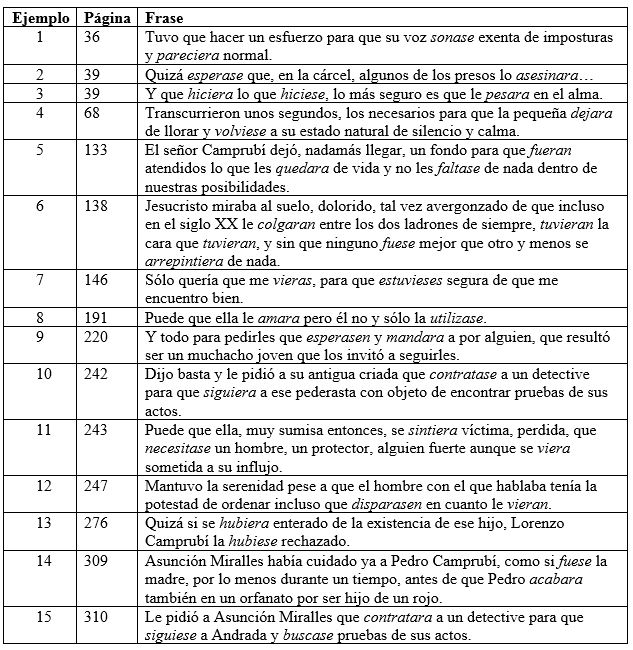

The Spanish in Algunos días also strikes familiar notes. I’ve previously written about Sierra i Fabra’s ample leísmo and his use of both the -ra and -se imperfect subjunctives, sometimes juxtaposed in a single sentence. The book includes two or three instances each of the verb restar and the noun horma, both old favorites of mine. Beyond these details, I got a kick out of following the often elliptical Spanish in the book’s many casual conversations between Mascarell and his partner David Fortuny, such as the following:

| Mascarell: Venga, vamos. Fortuny: Pero déjeme a mí, ¿eh? Mascarell: Toda suya. |

| Mascarell: ¿El arma? Fortuny: Ni rastro. |

| Fortuny: Caray, usted impresiona, ¿eh? Sin decir que es policía, la gente se lo suelta todo. Mascarell: Quien tuvo, retuvo. |

| Fortuny: Una chapuza. Mascarell: Más bien sí. Fortuny: Pero contando con lo aislado que está esto y que nadie sabe mucho de Romagosa… Mascarell: Lo lógico es imaginar que nadie daría con el cadáver en días, semanas, incluso meses. Fortuny: Mascarell, ¿por qué habla en plural? “Lo mataron”, “lo arrastraron”, “le quitaron”… Mascarell: Deformación profesional. No me haga caso. |

Reading exchanges like these is like watching a Spanish movie, but without the challenge of understanding rapid speech!

[Spoiler alert!!]

For me, however, the most intriguing bit of Spanish in the novel was the following sentence, which means ‘Concepción Busquets hired them to solve the case and died a few hours later,’ and appears just after Mascarell and Fortuny learn about Busquets’s murder.

Concepción Busquets les encargaba resolver el caso y moría a las pocas horas.

It struck me as bizarre that the verbs encargaba and moría are in the imperfect past tense, which Spanish normally uses to describe ongoing events or to provide background information. Moría, for example, would usually be translated as ‘was dying’ or, in another context, ‘used to die.’ I would expect this sentence to be written instead in the preterite past tense, which is normally used for sequences of events, i.e.

Concepción Busquets les encargó resolver el caso y murió a las pocas horas.

or perhaps

Concepción Busquets les había encargado resolver el caso y murió a las pocas horas.

thus combining the pluperfect había encargado ‘had hired’ with murió ‘died’.

I consulted a variety of sources to solve this riddle, and was amazed to find out how many tertiary uses the imperfect has. The Real Academia Española’s authoritative Nueva gramática de la lengua española describes several less-common uses of the imperfect, none of which accounts for the Concepción Busquets example:

- the imperfecto onírico o de figuración, which describe dreams (I knew about this, but it doesn’t apply here);

- the imperfecto de cortesía, which describes present actions politely (doesn’t apply here);

- the imperfecto citativo, which tactfully distances the speaker from a presumed fact he or she mentions (doesn’t apply here);

- the imperfecto prospectivo, which talks about things that were going to happen (doesn’t apply here);

- the imperfecto de hechos frustrados, like the former use but applied to events that didn’t actually happen (doesn’t apply here);

- instead of the conditional in the “then” part of an “if…then” sentence (doesn’t apply here).

- The Gramática‘s example of the imperfecto de interpretación narrativa, which describes an action that follows another, is eerily similar to the example at hand: Apretujó mi mano con su mano sudorosa y a los dos días moría ‘She grasped my hand with her sweaty hand and died two days later.’ However, this explanation would leave encargaba unaccounted for.

I had better luck with Ronald Batchelor and Christopher Pountain’s Using Spanish, which points out that “the imperfect is often used in journalistic [officialese] in place of the Preterite.” This could apply in the case at hand, since Mascarell is stepping back and summing up the state of the case. However, my favorite interpretation comes from a native speaker on reddit.com/r/Spanish who thought the imperfect in this context expressed irony. That’s a perfect fit, but I wish I could cite a published work rather than a miscellaneous redditor.

So, all in all, a difficult sentence. I welcome additional theories.

As a final note, Sierra i Fabra’s afterword includes his chronology in writing this 313-page book. He outlined it in five days and wrote it in eighteen. ¡Caramba!