My second book, Bringing Linguistics into the Spanish Language Classroom: A Teacher’s Guide, is progressing toward its March 30, 2021 publication date. Although the book hasn’t yet shown up on Amazon it is already available for pre-sale at a 30% discount on Routledge’s website. There you can also see the Table of Contents, which is essentially a list of the linguistic topics the book covers.

To be perfectly honest, I originally conceived of this project as a way to promote my first book, my beloved ¿Por qué?. This is akin to having a second baby just so your first-born has someone to play with. (See also the plot of My Sister’s Keeper.) But like any good writer, or mother, I fell in love with the project for its own sake:

- as a way to share important information about Spanish with my fellow teachers;

- for the creativity required to design the in-class activities and take-home projects that accompany each linguistic topic;

- for the challenge of creating more than 300 PowerPoint slides that teachers can use along with the book;

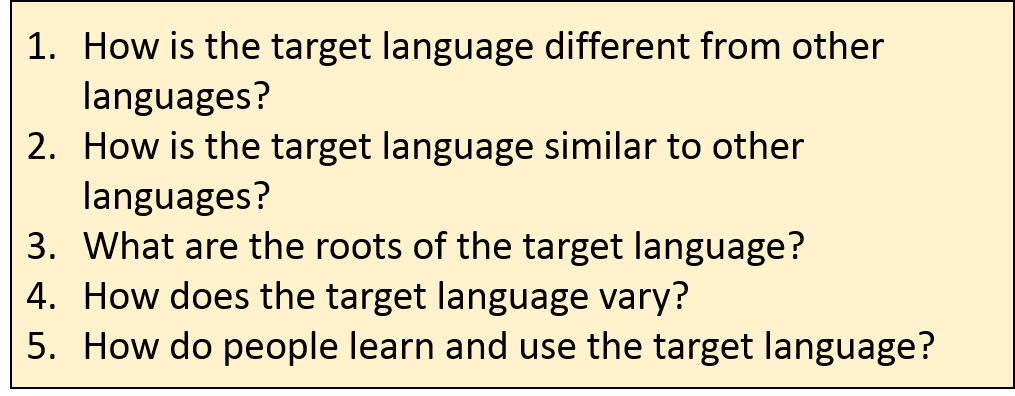

- as a way to promulgate the five “essential questions” for foreign language instruction I wrote about here;

- for the additional insights I gained into Spanish linguistics as I worked on the book.

I submitted my manuscript to Routledge at the end of July. At the end of September I resubmitted it after making some changes in response to a peer reviewer’s feedback. This step was very helpful, which is the whole point of academic peer review. For example, the reviewer pointed out that my section on the history of Spanish pretty much stopped with the conquest of the Americas (whoops), found some Spanish mistakes (¡Ay!), and suggested that I tackle the topic of preterite versus imperfect.

Routledge then turned the manuscript over to codemantra, a book production company based in southern India. (My contact there is a Tamil speaker.) They copy-edited the manuscript and sent it back to me for my own review, which I completed the day after Thanksgiving. I discovered some additional Spanish mistakes, such as a missing accent on marítimo, the invented word *colonista for colonizador, and closing punctuation placed inside quotes as we do in English, e.g. *La “a personal,” for La “a personal”, Between errors like these, and the English typographical errors the copy editor had turned up, I am forcibly reminded of one of my late sister’s favorite sayings, “There’s a reason why they put the word mistake in the dictionary.”

While all this was going on I was working with my Routledge editor on the book’s cover design. You can see the results in this blog’s right-hand sidebar, or click here. I found the speech bubble portion of the cover on the Getty Images website and thought it nicely evoked a classroom environment, The text I chose for the bubbles represents the range of topics and techniques in the book. I am a little worried about the legibility of the word rights in the rightmost bubble, but we weren’t allowed to monkey with Getty’s bubble colors.

Codemantra expects to send me the page proofs in mid-December. I will then have two weeks to create an index, a process I enjoyed when publishing ¿Por qué? There are professional services that will make an index for you but I can’t imagine anyone else understanding the book well enough to do an adequate job. That will be my last input before the book comes out in March.

Between each of these steps I have been working on a new research project regarding Spanish etymologies, which I hope to share with you soon, and also worrying about how to teach my first all-remote Spanish class starting in February. I have also purchased Instagram for Dummies and plan to put it to good use. So, lots to keep me busy!

Last September the NECTFL Review published my article

Last September the NECTFL Review published my article