The virtual ink was barely dry on my previous post, about the expressive power of Spanish adjective syntax, when I came across another great example. This one is from Puerto Rico, in Magali García Ramis’s tender-hearted memoir, Felices días Tío Sergio. (By the way, I would recommend this book to any reader looking for a fairly straightforward read. Not too heavy on vocabulary, a strong narrative line, and only 160 pages long!)

Referring to Tío Sergio, García writes: “Él decía que nosotros éramos únicos porque éramos los únicos tres con ojos verdes en la familia.” (p. 85) [He said that we were unique because we were the only three people in the family with green eyes.] In this sentence García is playing with the two position-dependent meanings of the word único. Before a noun — or, here, the number tres, which acts as a pronoun in this context — the adjective único serves as a quantifier, meaning ‘only’. After éramos (a form of the verb ser ‘to be’) the adjective takes its basic meaning of ‘unique’. This is the same meaning you would see if the adjective appeared in its basic position immediately after the noun, as in un libro único ‘a unique book’.

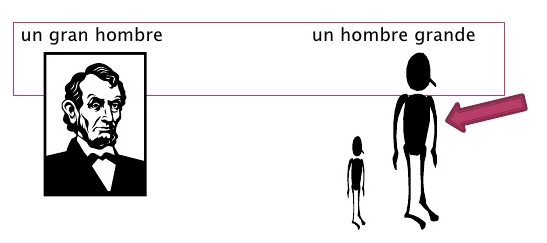

This is a familiar pattern, by the way. Other adjectives show their basic meaning both after a noun and after ser (or estar, another verb meaning ‘to be’). For example, alto can refer either to physical or metaphorical height. The core meaning of physical height comes through in contexts like un árbol alto ‘a tall tree’ or el árbol es alto ‘the tree is tall’, while the metaphorical meaning requires the before-the-noun position, e.g. un alto funcionario ‘a high-placed bureaucrat’. Another example is un viejo amigo ‘an old friend’ (of long standing) vs. un amigo viejo ‘an old (elderly) friend’. Only the second meaning is possible in the sentence mi amigo es viejo. Likewise, adding muy ‘very’ or other modifiers forces the core meaning: muy alto ‘very tall’ or bastante viejo ‘quite old’ can only refer to height and age.

I guess one could describe a book as being muy único ‘very unique’ also — as in English, this would be good grammar, but bad writing.