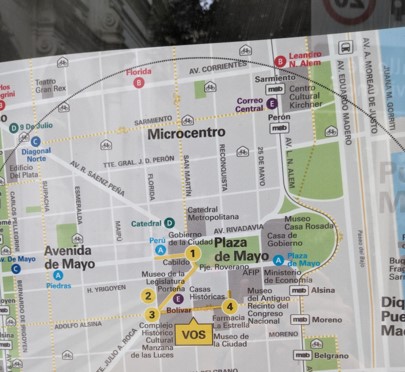

The street map below, which I saw on a downtown Buenos Aires signpost, captures the linguistic “Alice in Wonderland” vibe I experienced on my recent trip to Argentina. The VOS ‘you’ in the yellow box south of the Plaza de Mayo on the map was intended as a “You are here” location marker. However, as I explained in my previous post, voseo — the use of vos instead of standard Spanish tú — is a hallmark of Argentinian Spanish, as well as certain other Latin American dialects. So to me, this map told me that “I was here” linguistically — in the heartland of voseo — as well as geographically.

I was accustomed to seeing vos and its associated verb forms in Latin American novels, but spotting and hearing them ‘in the wild’ was a real thrill throughout my trip. As soon as I arrived at Buenos Aires’s Ezeiza airport I saw posters like the ones below, whose vos command forms tell the traveler to ‘connect yourself’ with WiFi, and ‘tempt yourself’ with the airport’s delicious food.

Later in my trip I was tickled pink to glimpse this large “VOS” featured on a branch office of the insurance company “La Segunda.” (I snapped this cell phone picture through a taxi window, hence the funny angle.) Its slogan Lo primero sos vos ‘You are first’ tells customers that they are the company’s top priority.

Although I’ve known about voseo forever, I had never had a good reason to actually learn the relevant forms. So before my trip I gave myself a crash course. I was surprised to see that in most cases, the only distinction between standard Spanish tú forms and their corresponding vos forms is stress. Specifically:

- In standard Spanish, present tense tú forms like amas ‘you love’ and comes ‘you eat,’ as well as informal (tú) command forms like ¡Ama! ‘Love!’ and ¡Come! ‘Eat,’ all stress the next-to-last syllable. Because this is the standard stress pattern for Spanish words that end in a vowel or s (think cuchara and cucharas), they are written without an accent mark.

- Vos forms display the opposite pattern. As illustrated by present-tense amás and comés, and commands ¡Amá! and ¡Comé!, these words are stressed on the last syllable, and therefore require a written accent mark.

As soon as I saw the Conectate and Tentate posters illustrated above, I realized that the final stress on vos commands further complicates an already challenging topic in Spanish: the use of accent marks in command forms with pronouns.

- In standard Spanish, the next-to-last stress of tú commands like ¡Ama! and ¡Come! is heard in formal and plural affirmative commands as well (¡Ame! ¡Amen! ¡Coma! ¡Coman!). In written Spanish, when you add a pronoun to any of these commands, you must also add an accent mark to maintain stress on what is now the third-to-last syllable. Some examples are informal ¡Cómelo! ‘Eat it!’, formal ¡Levántese! ‘Get (yourself) up!’, and plural ¡Escríbanles! ‘Write (to) them!’

- In contrast, because vos commands are stressed on the last syllable (e.g. ¡Conectá!), adding a pronoun means that you can drop the accent mark, since the stressed syllable is now in the usual next-to-last position (¡Conectate!).

- This means that Argentinians need to add an accent mark when adding pronouns to formal and plural commands like ¡Levántese! and ¡Escríbanles!, but remove an accent mark when adding a pronoun to informal (vos) commands like ¡Conectate!.

This situation is guaranteed to confuse anyone but a linguist! Not surprisingly, many Argentinians (incorrectly) omit the accent mark in formal commands with pronouns because they are used to doing this in informal commands. (I don’t know what the situation is with plural commands, which are less common.)

Below are two examples of such errors from our trip to Igauzú. The seatback airline safety instructions on the left omitted the accent mark on abróchese ‘buckle.’ (As you can see, I added it with a pen mid-flight, in the spirit of Deck and Herson’s self-righteous but inspirational The Great Typo Hunt.) Likewise, the informational panel on the right, from the Iguazú waterfall park, omitted the accent mark on acérquese ‘approach.’ Note that the safety instructions and the informational panel correctly accented cinturón, más, and información, implying that the missing accent marks on the commands were a sign of weakness in grammar rather than an overall spelling deficit. The missing accent mark on the subjunctive verb form esté (which I also wrote in myself) supports this conclusion.

Finally, I can’t help but ask: since tú verb forms, which are mostly used in the Northern hemisphere, have the opposite stress pattern from and vos forms, which are mostly used in the South, could this possibly have something to do with the Coriolis effect?

Just joking!

Stay tuned for my next fish post, four years from now.

Stay tuned for my next fish post, four years from now.