After taking some weeks off for summertime fun with my family I am now back to research for my third book. I’ve continued to work my way through David Crystal’s The Story of English in 100 Words — still inspirational and intimidating. But I’ve also taken a detour to devour Laura Spinney’s book Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global, about the pre-history of the Indo-European languages. I will definitely want to touch on this topic in my book, since it’s part of the history of Spanish.

For those of you who may be unaware, the Indo-European language family includes thousands of languages spoken today: Romance languages like Spanish, Germanic languages like English, Slavic languages like Russian, Baltic languages like Lithuanian, and Celtic languages like Welsh; Greek, Albanian, and Armenian; Hindi and other languages of northern India; and languages of Central and Western Asia including Pashtun (Afghanistan) and Persian (Iran). It also includes languages that are no longer spoken and (unlike Latin) have no spoken descendents. These include Oscan and Umbrian ( “Italic” languages related to Latin), languages of ancient Turkey including Hittite and Phyrgian (“Anatolian” languages), and Tocharian A and B, once spoken in the Tarim Basin of northwestern China.

I learned about the Indo-European language family as an undergraduate and graduate linguistics student. However, my knowledge of the family’s origins was vague: I knew only that it arose somewhere north of the Black Sea. (Or was it the Caspian Sea???) Although I was aware that in the years — decades, really 😉 — since I completed my PhD, there had been substantial new research on this topic, I hadn’t followed the field.

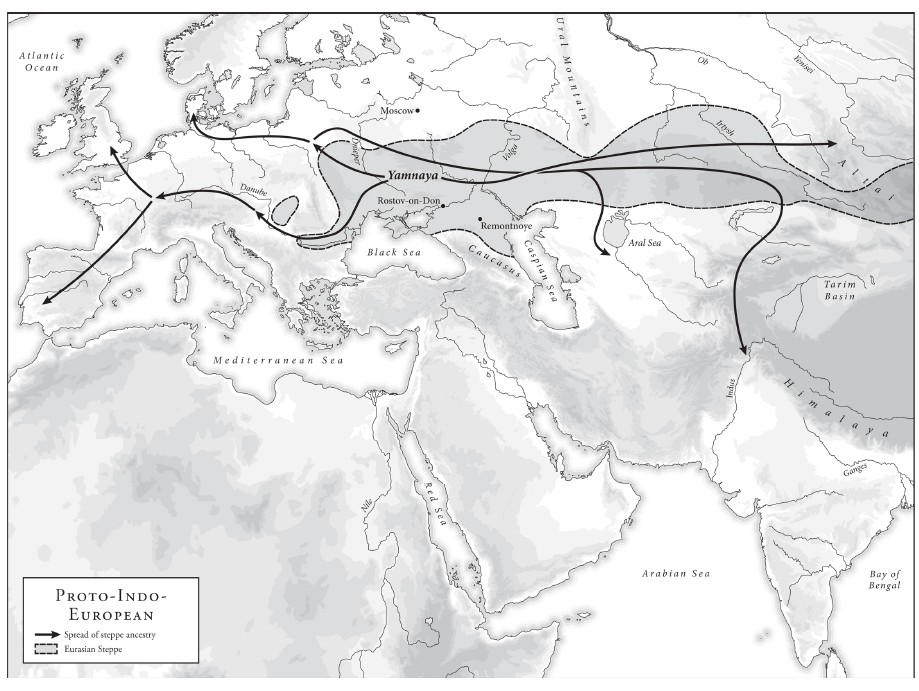

Proto has brought me up to date — and can I say “Wow?” Spinney’s book combines recent research from linguistics, archaeology, and genetics (DNA analysis) to illuminate what is known today about the origin of the Indo-European languages. Essentially, Proto-Indo-European — the common ancestor of the language family — spread east and west through the Eurasian steppe (grasslands), conveyed by cattle herders equipped with horses and wagons. The steppe was a natural environment in which such people could thrive and spread. Researchers call these steppe herders the Yamnaya, which means ‘pit grave’ in Russian, because of their burial practices.

The illustration below, from pp. 60-61 of Spinney’s book, shows the progression of Indo-European (black arrows) through the steppe (shaded area) and beyond. My vague memory wasn’t that far off, since the arrows show a specific point of origin in the steppe north of the Black Sea.

Genetic analysis of DNA from Yamnaya remains suggests an exciting possibility:

“The earliest Yamnaya males … carried a very narrow cluster of Y chromosomes. Later on, after the population had grown, other Y chromosomes entered the mix, but the first of their kind may have been closely related to each other on their father’s side. One way to interpret the evidence is to think of the Yamnaya as a single clan or brotherhood who distinguished themselves by their burial rite. They may have left a larger group, or been expelled from it, and having moved out of their ancestral valley became increasingly nomadic unril they vanished into the grasslands for good. If that is who they were it prompts an extraordinary reflection: fewer than a hundred people may have spoken the dialect that gave rise to all extant Indo-European languages.” (p. 69)

While Proto doesn’t have anything to say about Spanish specifically, it does include interesting speculation about the connection among Italic, Germanic, and Celtic languages:

Germanic, Celtic and Italic are related by common descent. This is evident from their grammar, their pronunciation and their core vocabulary (English – – father mother brother; Old Irish athir – máthir – bráthir ; Latin pater – mter – frter). But the relationships between them aren’t equal. Celtic and Italic are generally considered to be closer to each other than either is to Germanic, like twins with a third sibling.…Some linguists suspect that Italic and Celtic arose as a single, possibly short-lived language, Italo-Celtic, while Germanic arose separately.

As I had hoped, Proto provided me with the information I need to write about Indo-European origins. On other counts, as a linguist I especially enjoyed learning about Anatolian and Tocharian, two branches of the Indo-European family that had always flown under my cognitive radar. I think that many people interested in languages or history would find the book to be an informative and accessible read. It provides a dizzying overview of the early history of humanity around the Black Sea: a region that, like the Fertile Crescent, would be a springboard for widespread advances in civilization for millenia to come. I recommend it highly.