The title of this post is a shout-out to one I wrote back in 2014. That “linguistic gems” post described a nice stylistic use of the imperfect subjunctive in the Spanish novel La carta esférica, and a reminiscence about the trilled r from the Puerto Rican novel Felices días tío Sergio.

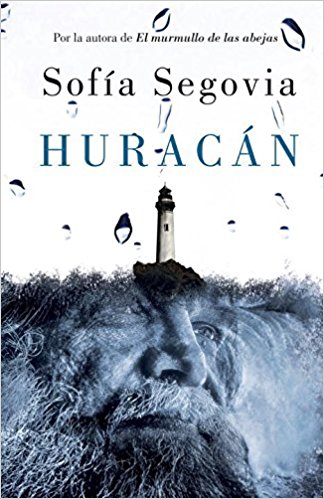

Today’s gems come from the Spanish-language novel that I’m currently reading, Sofía Segovia Huracán. It was this Mexican author’s first novel; she revised and republished it last year after the great success of her second novel, El murmullo de las abejas. I’m 50 pages into Huracán and completely hooked.

So far, Huracán is the picaresque tale of a Mexican boy who is given away (regalado) to a farmer because his family can’t afford to keep him. He eventually runs away and makes his living as a petty thief. I’m waiting for him to figure out how to redeem his life — and, of course, I’m waiting for the actual hurricane of the title.

In the meantime, I’m especially enjoying two aspects of the author’s Spanish. First, Segovia often puts into written form her characters’ “improper” Spanish, as shown in the selection below:

—¡Ya nos mandastes al demonio! ‘You sent us to the devil!’

—¿Adónde vamos? ‘Where are we going?

—Nosotros agarramos pa Tabasco. Tú lo matastes, tú te vas pa otro lado. ‘We’re heading for Tabasco. You killed him, you go the other way.’

The preterite past tense forms mandastes and matastes here have a final -s added to the standard forms mataste and mandaste. This is a very natural extension of the final -s that ‘you’ forms have in all other verb tenses, such as matas ‘you kill’, mandarás ‘you will sent’, and mandabas ‘you used to send’. I’ve read about this phenomenon but have never seen it in print. Pa as a shortened version of para ‘for’ that is common in colloquial Spanish in several countries, including Mexico. I’ve seen it written elsewhere as pa’.

The other aspect of Segovia’s Spanish that I particularly enjoy is her deliberate and even playful exploitation of some of the grammatical contrasts that are a Spanish instructor’s bread and butter. In this sentence, about the protagonist’s time in a street gang, Segovia plays with gender:

Aniceto no estaba acostumbrado a tanta orden y tanto orden. ‘Aniceto wasn’t used to so many orders and so much organization.’ (“command and control’?)

Orden is one of a set of Spanish words whose meaning changes with its gender; some other examples are el capital ‘money’ and la capital‘, el cura ‘priest’ and la cura ‘cure’, and el coma ‘coma’ and la coma ‘comma’. You will find a longer list here.

Also on the subject of the street gang, Segovia plays with the por/para contrast:

Si no era [el jefe] él quien hacía cumplir su ley, era el resto del grupo el que lo hacía por él y para él. ‘If the gang leader didn’t make Aniceto obey, the rest of the gang would do it in his place and for his benefit.’

The Spanish version is much more elegant, ¿no?

I’m looking forward to unearthing more gems as I make my way through Huracán!