Last month I was among the hundreds of high school and college Spanish instructors who convened in Cincinnati, Ohio to grade Spanish Advanced Placement (AP) tests. [AP tests are a way for U.S. high school students to earn college credit and/or impress the colleges they apply to.] Half the test is multiple choice and is machine-graded. The rest of the test — two speaking tasks and two writing tasks — is graded by humans. I was on the team that graded the writing tasks.

I hadn’t seen an AP Spanish test since I took one as a high school senior! Since then, the test, and its corresponding high school classes, have been divided into two: Spanish Language and Culture, and Spanish Literature. My colleagues and I were in Cincinnati to grade Spanish Language and Culture; the Spanish Literature exam was graded earlier in the month. We were in Cincinnati along with graders for the other Language and Culture tests — Chinese, French, German, Italian, and Japanese — and, oddly, Music Theory. This all took place at the gigantic and soulless Duke Energy Center in downtown Cincinnati.

I applied to be an AP grader a few years ago because my best friend had told me that her own work as an AP economics grader had been a great way to meet colleagues from around the country, and was also a lot of fun. This was the first year the timing worked out for me to participate, and I have to say that my friend was right. According to our orientation, our group included educators from all fifty states, and Spanish speakers from every Spanish-speaking country. It was great to get to know some of them. And the work itself was fascinating.

You don’t sign up for something like this unless you really like grading. I certainly do: it’s always interesting to see what students get right and wrong, and to get a glimpse of their thinking. This experience was, of course, very different from grading my own students’ papers. The main difference was volume. In my own teaching I never have to grade than a couple of dozen papers at a time, or for more than a few hours at a time. In Cincinnati we graded hundreds of papers, working from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm for seven days in a row. Even with morning, lunch, and afternoon breaks, it was hard to keep up one’s energy and attention. It helped that there were no distractions, and that a strong esprit de corps reigned in our giant grading room (Exhibit Hall A). Keeping the good of the test-takers in mind, we aimed to grade the last essay of the day as carefully as the first.

Another difference was that we weren’t grading our own students’ work. It felt strange to be reading essays with a completely blank slate instead of knowing who the students were. This made for a more objective review, however, and is one reason why AP tests are graded centrally instead of by each student’s teacher. it also meant that grading was a single, unidirectional event instead of part of an interactive process. Normally I grade with red pen in hand, pointing out different types of errors for students to fix in a second draft. As an AP grader I wasn’t allowed to annotate the essays I read, or to make notes, even for my own benefit.

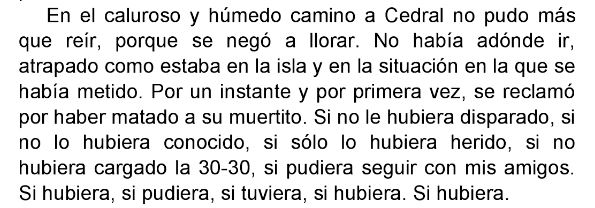

A final difference was the type of Spanish in the essays. Most of my students speak English as a first language, and I’m used to reading essays with this population’s typical errors. In contrast, many — or most (65%), according to Wikipedia — AP Spanish test takers are native Spanish speakers. A good fraction of these have not fully mastered the ins and outs of Spanish spelling, despite a year or more of formal study of their language. This means that these essays had a different set of errors: those of someone who has learned Spanish by ear. Typical errors were missing or misapplied accent marks, missing or overused silent h, the substitution of d for r (e.g. pedo for pero ‘but’), and the confusion of ll and y and likewise b and v. (See this earlier blog post for historical examples of the same errors.) I was amazed to see that two students even misspelled the ubiquitous word yo ‘I’ as llo.

The good folks from the College Board did a phenomenal job administering the grading process. This involved recruiting, transporting, housing, and feeding the graders; keeping track of the exam papers; and — most importantly — training the graders so that our scores were calibrated. We spent hours learning how to grade each of the two writing tasks, following a detailed rubric, and had refresher training sessions after each break. Each table of seven graders had a head grader who answered our questions and spot-checked our work. As far as I could see, colleges evaluating AP test results should feel confident that the scores are reliable.

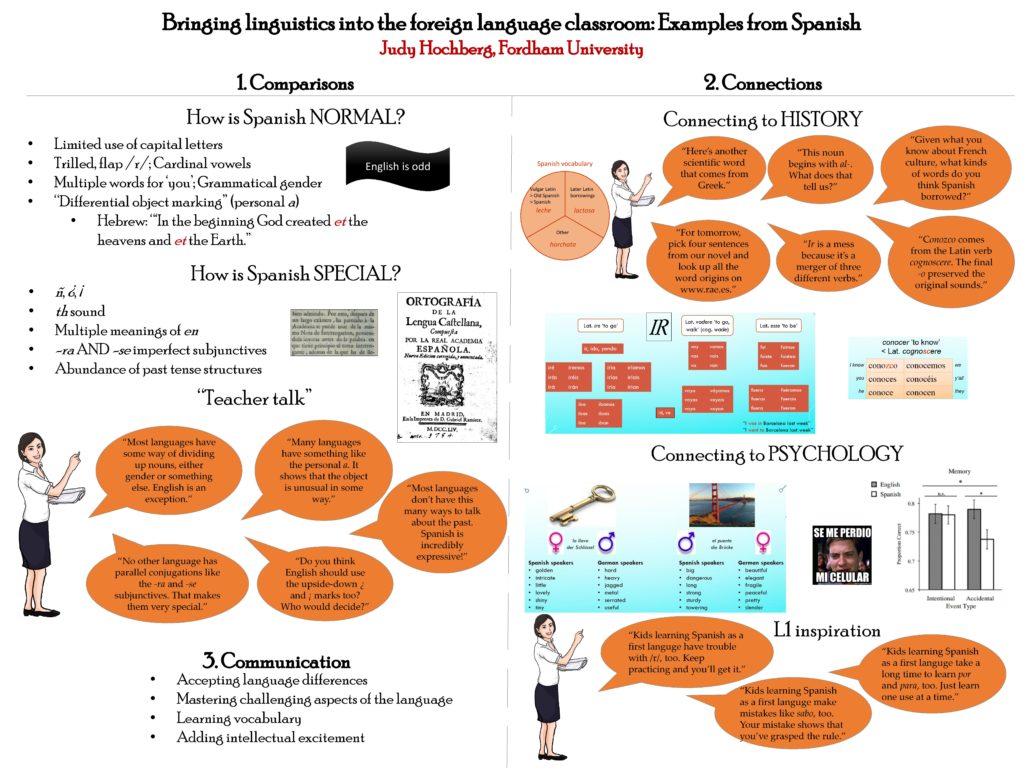

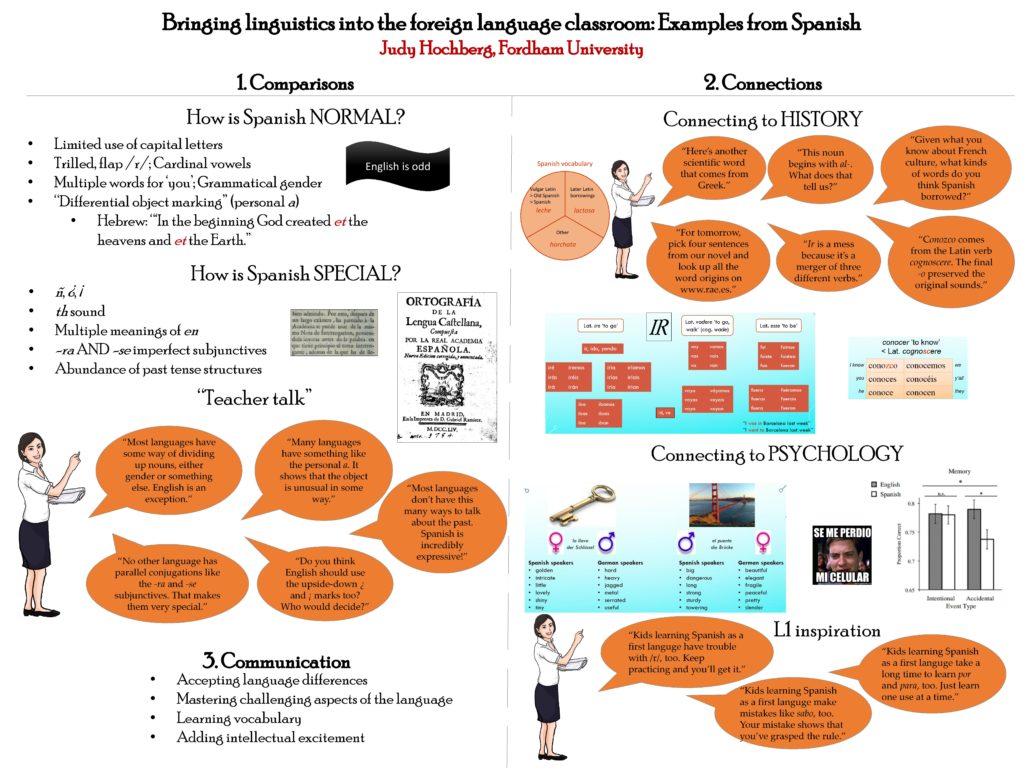

One night during the week was “Professional Night”, and my poster on “Bringing linguistics into the foreign language classroom” (see below) was accepted for the night’s mini-conference. It was well received, and I sold the few spare copies of my book that I had with me. Hooray!

A technical note: I made the poster as a single PowerPoint slide, sized to 4 x 3″, and used “Export PDF” (under the “File” menu) to create the image.