My friend Sue and I are now in the second week of our linguistic tour of northern Spain. Yesterday we hiked up to the fortress overlooking the city of Burgos and its Arlanzón River, and thus back in time to the early centuries of the Reconquista (details here). Today’s two excursions, to the Catedral de Burgos and the Monasterio de las Huelgas, carried us forward several centuries, through the era of El Cid, the political consolidation of most of Spain, and the successful pursuit of the Reconquista.

The Cathedral is built on a site of great linguistic interest: in 1080, the Council of Burgos took place in an earlier church at the same site. As described in this previous post, the purpose of the Council was to enforce the use of the Latin Mass in place of the vernacular that had sprung up in Spain. While touring the Cathedral today, I learned that just one year later, in 1081, the city of Burgos became the official seat (sede) for the province’s bishopric, or diocese. Clearly the Council had increased the city’s prestige: language matters! The first Cathedral of Burgos was built over the next fifteen years.

Informative sign from Catedral de Burgos, showing establishment of Burgos as religious seat one year after the Council of Burgos.

Another informative sign, dating the original Cathedral to within fifteen years of the Council of Burgos.

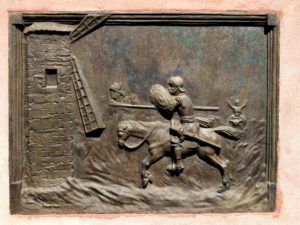

Today’s Cathedral is of further linguistic interest because it houses the tomb of El Cid, the Reconquista hero of the epic poem that is the first known work of Spanish literature. The tomb’s inscription includes the Latin version of El Cid’s name (Rodrigo > Rodericus) and that of his wife, buried with him (Jimena > Eximena). Above the cross you can also see a key line from the poem: a todos alcanza honra por el que en buen hora nació: very roughly, ‘everyone gained in honor because this good man lived’.

Tomb of El Cid and his wife Jimena in the Catedral de Burgos

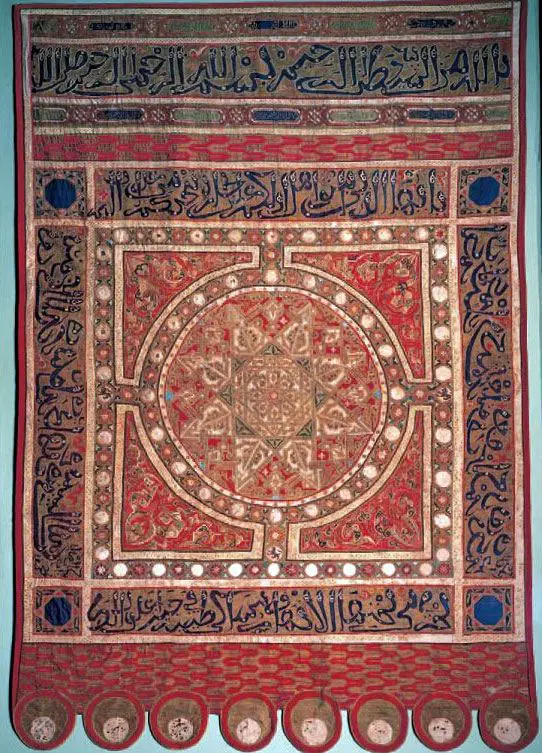

Our second touristic destination of the day, Burgos’s Monasterio de las Huelgas, fast-forwarded us less than a century to the year 1187. The Monastery was founded by Queen Leonor, the British-born wife of Alfonso VIII of Castilla, and serves as a pantheon, or royal burial place, for this couple and their descendants. By Alfonso’s reign the Reconquista was going full blast, carrying the Castilian language with it. The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, a turning point in the Reconquista, took place in 1212; a spectacular door hanging from the tent of Alfonso’s Moorish opponent, Muhámmad al-Násir, hangs in the Monastery’s Museo de Ricas Telas Medievales. It is a harbinger of the eventual fall of Granada at the hands of Alfonso and Leonor’s descendants, Ferdinand and Isabella, and thus the final victory of Castilian Spanish.

Pendón de Las Navas de Tolosa

Valladolid was our stopover en route from Salamanca to Burgos, and well worth a visit. Its star attraction is the

Valladolid was our stopover en route from Salamanca to Burgos, and well worth a visit. Its star attraction is the