Look for more red ‘ink’ below to understand the “ain’t” in this post’s title.

My Spanish students often have difficulty telling the difference between direct and indirect objects. They say things like Quiero conocerle ‘I want to meet him‘ (instead of Quiero conocerlo) or, conversely, Lo di el libro ‘I gave the book to him‘ instead of Le di el libro. I inevitably have to assign students helpful activities like this one to attune their ‘ear’ to this often subtle difference.

The first of these ‘errors’ (conocerle) is ironic because for many Spanish speakers it is perfectly normal Spanish. Leísmo — the substitution of le instead of lo for masculine direct objects that are human — is a widespread Spanish pattern, especially in Spain. In fact, leísmo is a long-established object pronoun pattern, rather than a recent development (as many native speakers assume). In this regard leísmo is akin to English ain’t, which was a widely accepted expression of negation (beginning in the 1700s) before it became stigmatized. (See David Crystal’s The Story of English in 100 Words for details.)

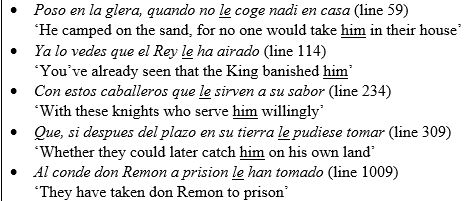

I’ve recently researched the history of this transformation (for leísmo, not ain’t). Leísmo certainly goes way back: consider these leísta examples from the 13th century epic poem El poema de mío Cid:

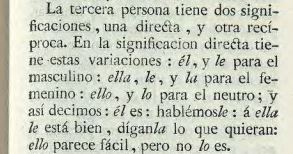

What truly impressed me was the official embrace of leísmo. The first edition of the Real Academia Española’s (RAE) grammar guide, published in 1771, was exclusively leísta: it required le as both a direct and an indirect object masculine pronoun (note also the endorsement of laísmo in díganla lo que quieran):

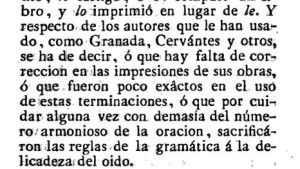

The first mention of lo as a direct object masculine pronoun was in the 4th edition of the RAE grammar, published in 1796. In this edition the grammarians adopted a sarcastic tone, speculating that non-leísta writers must have had a bad copy editor, or been careless, or had “sacrificed the rules of grammar to satisfy the ear”.

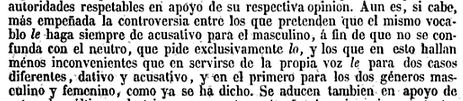

Between 1796 and the fifth edition of the RAE grammar in 1854, the Valencian linguist Vicente Salvá and the Venezuelan linguist Andrés Bello published their own, influential grammars. Salvá proposed, and Bello adopted, the compromise position that is so widespread today: le for human masculine direct object, lo otherwise. Under the influence of these In the 1854 edition the RAE changed their posture. First, they presented both sides of the leísmo argument:

This sentence is a doozy! I practically had to diagram it to finally understand it as: “The most intractable controversy is between those who favor the use of le as a masculine direct object pronoun, to avoid confusing such objects with the abstract ones assigned to lo, and those who find this potential confusion less of a problem than the use of le for direct and indirect masculine objects as well as feminine indirect objects.” (By “abstract” they mean pronoun uses like Lo siento, where lo doesn’t refer to a specific object.) The grammarians went on to praise, though not explicitly endorse, the Salvá/Bello compromise, an attitude maintained today:

I have to conclude with a thank-you — from the bottom of this researcher’s heart — to the RAE, and to the various libraries that have cooperated with Google, for making these original sources available on the Internet.

If you enjoyed this post, make sure to vote for spanishlinguist.us in the ongoing Top 100 Language Lovers poll! (through June 14).

Interesting post. I’ve wondered the extent to which nonstandard (ish) forms are stigmatized in Spanish by native speakers. The Spanish I studied in high school and college was extremely formal and well-pronounced by my professors. Talking with average native speakers, however, was a different story.

You say that the degree of stigma for being ‘leista’ is equivalent to prescriptivist perception of the use of ‘ain’t’ in English. How would you say the conservative / more educated / upper class speakers view things like ‘pa’ for para and other contracted forms?

“Ain’t” is, I think, considerably more stigmatized than leísmo. The Real Academia accepts leísmo within certain bounds — for singular, human entities, essentially the Salvá compromise — whereas I doubt any standard English grammar accepts any flavor of “ain’t”. I’m less knowledgeable about things like “pa”; perhaps a native speaker can weigh in? They would certainly not be accepted in a college essay!

I think these are felt as being part of casual speech rather than the standard grammar, but I don’t know about the affective side of this judgment. You could try asking on /r/spanish.

Hola, Judy:

Sobre el leísmo se han hecho cientos o miles de tesis doctorales y podría dedicarse una carrera completa solamente para su historia. Mi perspectiva como hablante español y sureño (sevillano) es que el leísmo no se habría extendido jamás ni existiría siquiera si no fuera ‘gracias’ a la RAE. Ya en los albores del español, pronto surgió una mutación gramatical para los pronombres clíticos de tercera persona motivado por una simplificación del paradigma latino. Este cambio se produjo en Castilla, antaño el reino más poderoso de la península Ibérica que tradicionalmente ha detentado el poder económico, político y militar de España. Hay estudios sociológicos de la época que dan fe de que los máximos exponentes de la oligarquía castellana vieron en esta transformación vulgar una manera de imponer sus rasgos regionales y distinguirse otros pueblos considerados inferiores. Los colonizadores de América fueron andaluces y extremeños por orden den Castilla (pues eran los habitantes de más baja alcurnia) y buscaban formas de establecer diferencias estamentales.

Desde hace siglos mezclaron así la lingüística (en concreto, un solecismo) con el clasismo medieval: ser un leísta castellano era signo de estatus social y económico. Cada noble de las otras regiones pretendía emular las características de Castilla. Bajo este panorama se llegó al siglo XVIII, en el cual era tal la ceguera del etnocentrismo que los primeros miembros de RAE despreciaban y condenaban como incorrecto cualquier manifestación que no ocurriera en Madrid. De hecho, se evidencia hasta qué punto se comportaron sesgadamente al proclamar reglas del español que sólo acontecían a 10 km a la redonda desde donde se situaba dicha Academia.

Llegados al día de hoy, creo que la mentalidad profunda de los castellanos y la RAE no ha cambiado, únicamente se ha matizado para tratar de mantener la unidad panhispánica. En su fuero interno siguen siendo unos profundos etnocentristas incapaces de tolerar las variantes de otras regiones del modo en que ellos velan por las suyas. El leísmo está invadiendo toda la España y dentro de un par de décadas será la única variante en el país a causa de la influencia mediática: política, cine, televisión, traducción, literatura. Los medios transmiten la falsa idea de que el castellano es un español neutro penínsular. ¡Ni en un millón de años! La mitad del vocabulario que utilizamos en el sur resulta totalmente distinto; cada región presenta peculiaridades únicas y, precisamente, el dialecto castellano es uno de los más alejados a la etimología. Diría incluso que un escritor no leísta (como un servidor) debiera incluso cometer leísmo si no quiere que las editoriales capitales lo miren con ojos de pueblerino.

Yo desprecio el leísmo no por ser lo que es: una variante de los pronombres clíticos de tercera persona, sino porque es hasta hoy una arma arrojadiza y conquistadora propia del nacionalismo más profundo y vetusto. Ningún académico castellano debería creerse superior simplemente por serlo; sin embargo, la realidad cotidiana me demuestra lo contrario.

Un saludo cordial.

Atentamente, Adrián.

Gracias por su comentario erudito, Adrián.

Gracias a usted, Judy. Esta temática me suscita ciertos resquemores personales y, por ello, lamento quizás lo sesgado de mi explicación. Asimismo, con las prisas he cometido una serie de erratas, a saber: *por orden de*, *invadiendo toda España*.

Una vez más, le doy mis felicitaciones por el sumo trabajo que desarrolla con tesón y humildad.

Un saludo cordial.

Thanks for writing this — neat!

“The first mention of lo as a direct object masculine pronoun was in the 4th edition of the RAE grammar, published in 1796.”

Is there evidence of popular use before this? Is the use of ‘lo’ for masculine direct object pronoun modern? In that case, could leismo be thought of as an antiquated usage rather than a modern error?

Good questions! Yes, there is evidence of popular use before this: already in El Cid you see examples like Reçibiolo el Çid abiertos amos los braços ‘The Cid received him with both arms open’ and Prisolo al conde, para su tierra lo llevaba, A sos creenderos guardarlo mandaba ‘He took him, the Count, and carried him to his land, and ordered his followers to guard him’.

For your second question, yes, the point of the post is that leísmo can be thought of as a long-established usage (I’d say that instead of “antiquated”) rather than a modern error.

Hola, Judy:

Algo que me parece todavía más interesante que el leísmo es el fenómeno de la duplicación, documentado ya desde el Cid, y las consideraciones que hoy por hoy se hacen de su empleo, en términos de prestigio y corrección. Para qué decir de variedades en donde se documentan casos de pleonasmo de los clíticos de acusativo o de dativo. Carmen Silva-Corvalán, que mencionaras en otro post, tiene un artículo esclarecedor sobre este último fenómeno, por si te interesara leerlo, y en su manual de 2001 (77-78) lo reseña brevemente.

Saludos,

Antonieta, solo hoy vi su mensaje; por eso he demorado en contestar. Investigué la duplicación de los pronombres cuando escribía la sección correspondiente de mi libro. Para mí lo interesante fue la multitud de explicaciones sugeridas, desde la pragmática hasta la sintáxis y aun la influencia indígena. Si te interesa te puedo enviar una copia de esa sección.

Pingback: Jordi Sierra’s off-and-on leísmo | Spanish Linguist